Triggered by Light?

As the days have started getting longer, plants are waking up and preparing for the coming spring. While it might seem like they are responding to an increase in sunlight, plants actually use nighttime to track the changing seasons.

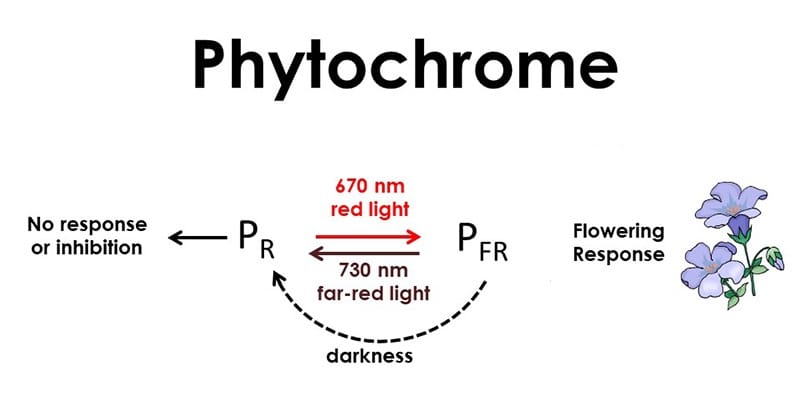

First and foremost, plants are highly evolved "light eaters" that have spent the past 500 million years refining a photosynthetic machinery that first arose 3.4 billion years ago. Over countless generations, plants have developed an extraordinarily sophisticated set of light-receptive pigments that can sense, evaluate, and respond to the quality, quantity, direction, and duration of incoming light. This ability is so important to plants that 25% of their genes are devoted to processing light signals.

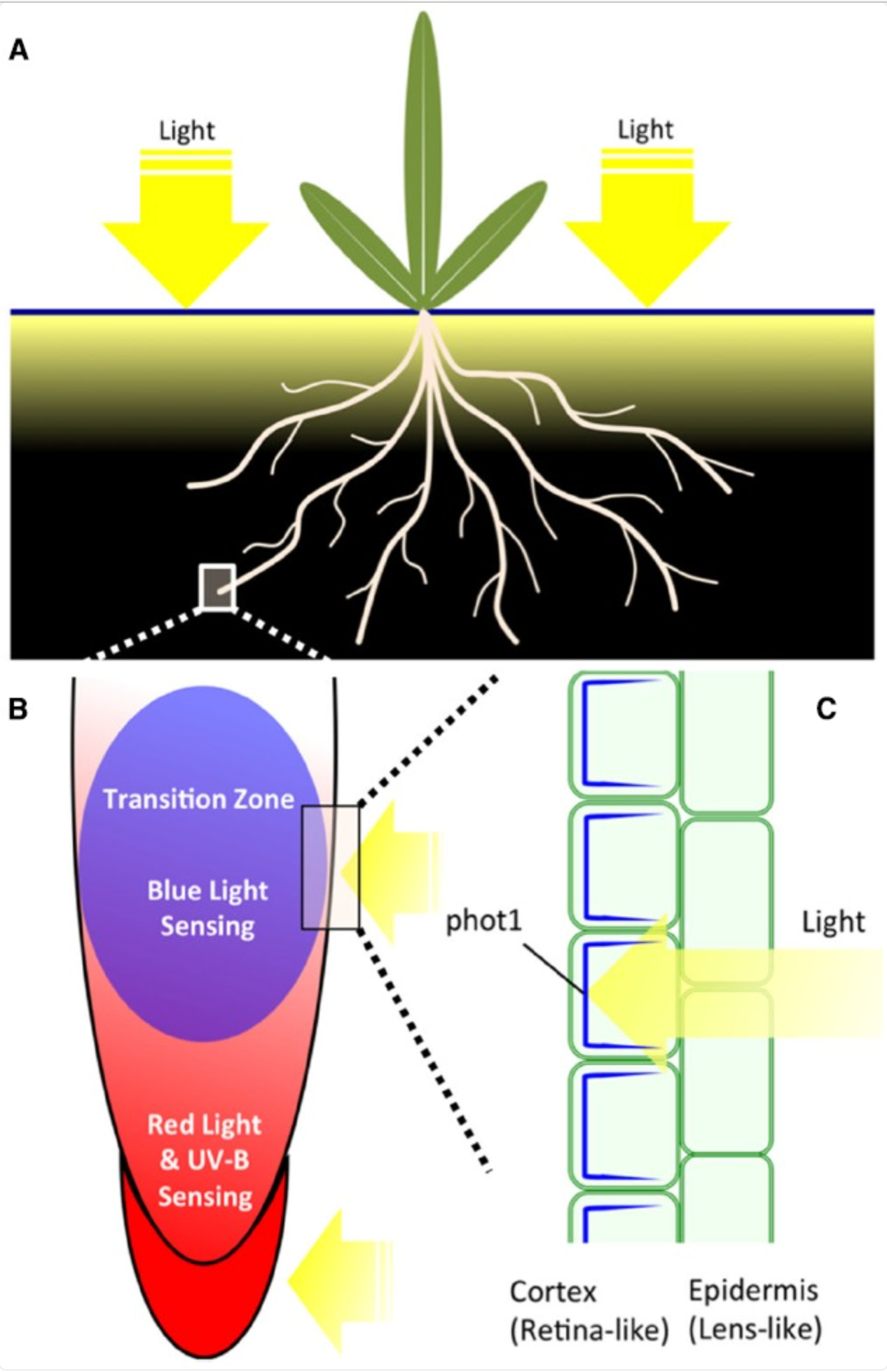

It makes sense then that these light-gathering mechanisms are phenomenally complex. In fact, the light-sensing proteins in plants are among the best studied plant proteins, yet we still have little more than a rudimentary understanding of how they work.

Briefly, these light-sensing proteins are called phytochromes, and what makes them particularly interesting is that they exist in two interconvertible forms. In the presence of sunlight, with a predominance of red wavelengths, phytochromes flip from a form known as PR to a form known as PFR. In darkness (either at night or in the shade), where there's a predominance of far-red wavelengths, phytochromes flip from PRF back to PR.

Plants use the ratio of PR to PFR to track the changing seasons and conditions around them, and to make things even more complicated, plants have five types of phytochromes that give them an even more nuanced reading of light conditions.

You might imagine that plants use phytochromes to measure sunlight, but in a series of elegantly designed experiments, scientists demonstrated that, contrary to popular opinion, plants track the changing seasons by monitoring the amount of PR that accumulates at night. And yet, the PFR that forms in daylight still matters because PFR is what triggers seed germination, growth, and other biological processes.

Again, this is an extremely complex topic, but at its core, phytochromes are simply "reading" the lengths of day and night, then acting as on-and-off switches that trigger a cascade of downstream processes. I liken it to walking into a kitchen and flipping on a light to make dinner; the light switch doesn't make dinner for you, but it unlocks a sequence of steps that lead to dinner being made.

In other words, switches are being turned on, and spring is on its way!

More Resources:

This is a greatly simplified version of this topic, and you can go much deeper if you're interested. This YouTube video is a brief and simple introduction to the topic, while this slightly longer video goes a bit more in depth. This technical paper, along with its extensive bibliography, offers a glimpse into how complex this topic really is (it also gives you a hint of the kinds of papers I have to read and translate in order to write these newsletters every week!).

Member discussion