Catkinology

Every spring you see them, and unless you're an allergy sufferer, you may only notice them briefly then promptly forget all about them. But as soon as you start studying catkins you'll discover that they play an outsized role in more ways than you might realize.

Let's begin by asking "What are catkins?" Catkins are slim clusters of flowers, with no petals, produced by willows, alders, birches, cottonwoods, oaks, and a few other types of trees. Remarkably, all the flowers in a catkin are the same sex (while flowers on most other plants contain both male and female parts), and some species include separate male and female catkins on the same plant, while other species have male and female catkins on different plants.

Densely clustering flowers around a single stalk is energetically efficient so it allows these plants to flower precociously, in other words they flower early in the spring before any leaves come out. This can also be a cold time of year, so you'll notice that many catkins are defended with furry coats that trap heat, hence the common name "pussy willows."

Many species that produce catkins are wind-pollinated and there's a tremendous advantage to flowering early because leaves block the movement of wind-borne pollen grains when they start emerging. Trees that produce insect-pollinated catkins also benefit from flowering before other plants bloom because they attract all the hungry pollinating insects.

Catkins are especially important for bumblebee queens and early-season bees. Photos by May Chen

Catkins play a significant ecological role because they emerge early and are loaded with proteins and vital nutrients at a time of year when these elements are in short supply. Not only are they critical for a huge number of pollinating insects, but catkins also attract many aphids, caterpillars, and gall-forming insects. Over 150 species of insects rely on willow catkins alone for their larval development, so it's no surprise that crab spiders have 25% higher hunting success when feeding around catkins.

Many other animals love catkins too. There is so much protein in catkins (18%) that squirrels prefer them over acorns. Black bears use them as a key source of phosphorus, potassium, and calcium and up to 85% of their diet in Alaska can be cottonwood catkins in April. Chickadees time their nesting to coincide with peak numbers of caterpillars on catkins. Ruby-crowned kinglets increase their foraging efficiency 40% when feeding around catkins, and ruby-throated hummingbirds follow "catkin corridors" during migration.

However, not only are catkins a vital resource when they're on trees, they also drive nutrient cycles when they fall to the ground and begin decomposing. Falling catkins can add 11-16 pounds per acre of nitrogen-rich litter to the forest floor (a single poplar produces about 55 pounds of catkins) with profound impacts on soil microbe communities. Earthworm populations increase 30% under catkin-producing trees, and populations of springtails can exceed 10,000 per square yard in layers of decomposing catkins.

There's another hidden story here, and it has to do with the locations where these trees grow. Super abundant, catkin-bearing trees like willows, alders, birches, and cottonwoods line nearly every stream and river from timberline to valley floor, dropping their catkins into the water in early spring when the aquatic food chain is in greatest need of nutrients and leaves haven't started falling yet.

Not only do catkins provide an enormous input of organic matter to streams, but they are also very high in nitrogen and very low in the secondary compounds that make leaves so hard to digest. In addition, decomposing catkins provide far more complex surfaces than flat leaves, offering homes and feeding sites for 2.5 times more invertebrates and microbes than leaves support.

As a final sidebar, catkins are also playing a major new role in the world of technology and it has to do with what happens after all those catkins begin dispersing clouds of seeds in the wind. Have you ever experienced cottonwood and willow seeds so thick they fill the air and pile up everywhere on the ground?

Cottonwood catkins mature into fluffy seeds that carpet the ground. Photos by David Lukas

This is a huge issue in Beijing, China, because the city planted two million trees in the 1960s and 70s to combat deforestation. These trees now produce over a billon pounds of fluffy seeds each year in the urban core alone and it's become a bit of a crisis. However, scientists searching for a solution discovered that the lightweight hairs on these seeds are hollow tubes with a remarkable range of industrial applications.

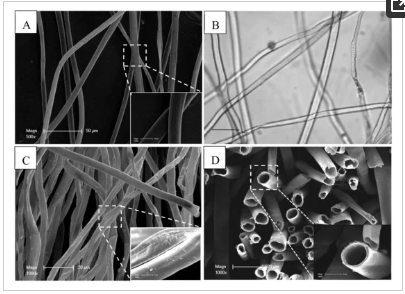

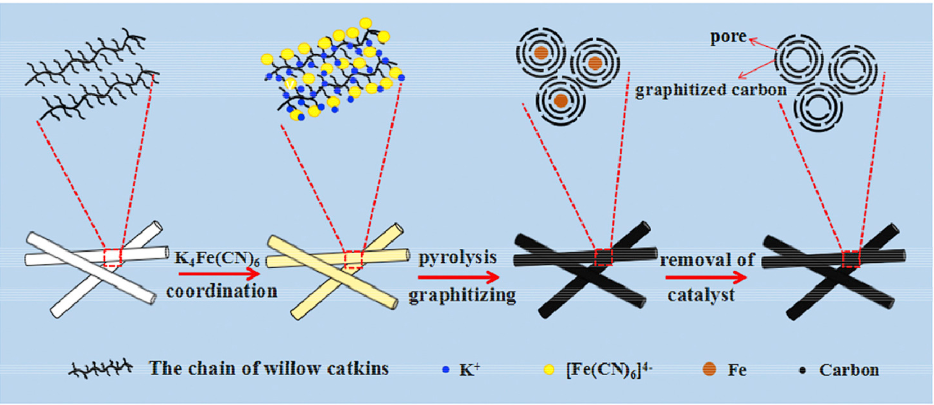

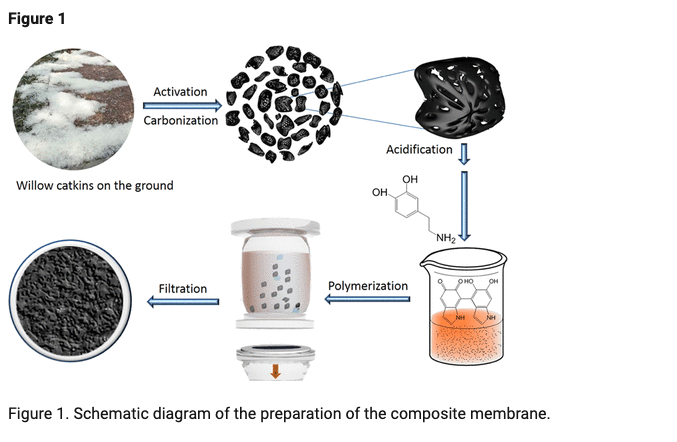

Electron microscope view of catkin hair tubes (from Wu et. al.) and diagram of process for converting organic catkin hairs into industrial tubes (from Zhang et. al.)

These organic nanotubes can be carbonized (converted from organic matter to durable carbon) to preserve their tubular structure then used for everything from soaking up atmospheric carbon and toxic waste, to building supercapacitors for the mass transport of electolytes in lithium ion batteries. Other researchers have used catkin tubes to build composite membranes that are highly effective at removing 99.9% of salt from seawater and 99.5% of heavy metals from wastewater, and even better, this process of creating pure water is powered by the membranes naturally absorbing and utilizing solar energy.

There's a lot more to mention, both in terms of ecology and technology, but I just wanted to give you a hint of what our catkin-powered world looks like.

Member discussion