Bone Closets

As mentioned in my recent newsletter on Liquid Skeletons, I'm in the middle of taking an online course about mammal bones being taught by David Moskowitz and Nyn Tomkins. The topic is fascinating, but it begs a critical question: where are all the bones?!

Not only am I thoroughly enjoying this amazing class on bones, but I also have half a dozen books on this topic, so I'm fired up and ready to head out on a walk and find some bones. However, the reality is that it's incredibly hard to find animal bones in the wild, and this strikes me as odd because bones are made of durable materials that can persist for hundreds or thousands of years. Millions of animals die every year, so why don't we find more bones?

Let's start by looking at why skeletons evolved in the first place. Complex, multicellular life started in the ocean about 800 million years ago. These early organisms had little structure, but oceans are saturated in calcium, so some of these organisms started building shells and other protective structures from these abundant calcium minerals.

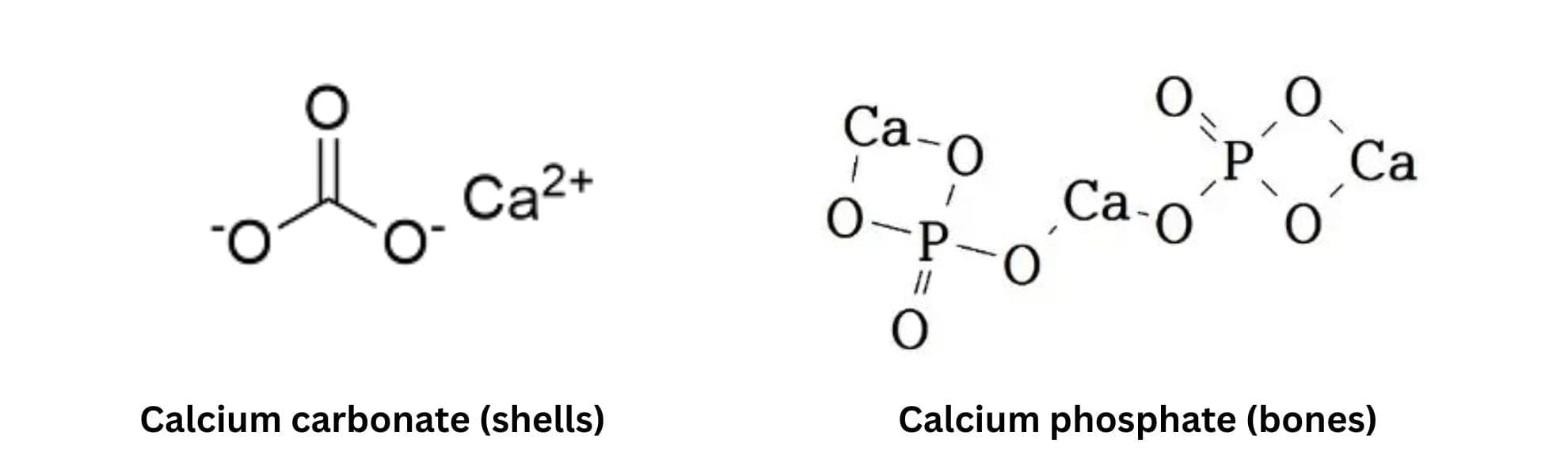

The advantages of having protective structures led to the Cambrian Explosion around 500 million years ago, when many complex animals, including the first vertebrates, suddenly appeared in the fossil record. The Cambrian Explosion also signaled a major shift from shells (built from calcium carbonate) to bones (built from calcium phosphate).

You might think that skeletons simply offer structure and support, but there's an even more important reason why bones matter. Animals with bones frequently engage in rapid, intense bursts of activity that produce lactic acid. Calcium carbonate breaks down in acidic environments, while calcium phosphate is largely resistant to acids, so this innovation means that bones allow animals to accumulate lactic acid while chasing down food or running away from predators.

Another critical reason why bones matter is that they are an efficient way to store hard-to-acquire minerals. In the ocean, calcium is abundant, so calcium is an ideal building material, but phosphorus (which is required for metabolism) is far rarer and mostly obtained through food. This meant that animals with bones had an advantage because they could store excess phosphorus (as calcium phosphate) when food was abundant, then draw on these stores in times of need.

Calcium phosphate offered another advantage when early vertebrates moved out of water and onto land. Phosphorus tends to be abundant in terrestrial environments, while calcium is rare, but bones can easily store both calcium and phosphorus (as calcium phosphate).

When you look at all the vertebrates of the world, and all the bones inside their bodies, you start to realize that this represents a highly significant pool of stored, hard-to-acquire nutrients that are vital for a wide range of life processes. For example, in order to grow antlers, a moose needs to eat an extra 1300 pounds of dry leaves to secure enough scarce minerals for this effort. That's clearly impossible, so a moose will draw from the calcium and phosphorus stored in its bones.

When antlers fall, or an animal dies and its bones are left behind, they become a resource for an entire web of life as these structures break down and release stored nutrients. Deer, rodents, carnivores, birds, and fish are some of the animals that eat bones, and on a microscopic scale, countless microbes and fungi acquire nutrients from bones. This concentrated release of scarce nutrients is so important and long-lasting that soils in archeological grave sites still show elevated levels of calcium and phosphorus after 4,500 years.

If you're talking about the bones of a single dead animal, the overall impact might be highly localized and relatively trivial, but scientists are now pointing to the widespread impacts that humans have had by reducing animal populations. For example, the loss of massive populations of turtles in the southeastern United States has led to rivers losing phosphorus. Salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest have declined over 93%, which means that far less phosphorus and other critical minerals are being transferred from the ocean to terrestrial ecosystems. And it's been estimated that when American bison were abundant, a single documented mass drowning in a Great Plains river contributed half of that river's annual phosphorus load.

Every animal needs calcium and phosphorus for critical bodily functions like muscle contractions, cell metabolism, cell membranes, and DNA production. It takes a lot of time and energy to collect and store these nutrients, so it makes sense that these storehouses of nutrients don't just lie around and go to waste.

Further Reading:

Here are two useful, technical papers on this topic: Long-term effects of buried vertebrate carcasses on soil biogeochemistry in the Northern Great Plains, and The vertebrate bone hypothesis: Understanding the impact of bone on vertebrate stoichiometry.

Member discussion