Whoa Mosquito

Every summer, for over 200 million years, mosquitoes have arrived in droves to torment the lives of warm-blooded (and even cold-blooded) animals—and this summer they are back in the news for all the wrong reasons.

Research now shows that across the United States climate change is increasing the number of warm days when mosquitoes can be active. And if you live in California you don't need to be told this because you'll have already noticed that epic winter rains, plus warm days, equals swarms of mosquitoes.

Perhaps even more disturbing, there's been a round of new malaria cases in Texas and Florida, where cases haven't been reported for over 20 years!

Mosquitoes get a bad rap, and for good reason, but they are also a fascinating and surprisingly complex insect that provide food for a vast number of both aquatic and terrestrial organisms.

It is thought that mosquitoes have killed more humans than any other animal, but only 100 kinds of mosquitoes out of the world's roughly 3500 species cause problems for humans.

Did you know that it would take about 1.2 million mosquito bites to drain all the blood from your body?!

And, please correct me if I'm wrong on this, but I think that in many cases mosquitoes aren't introducing new diseases to humans but are instead only carrying diseases from one infected human to other humans—which makes them more the bearer of bad news than the bad news itself.

Personally, I'm much more fascinated by things like the fact that mosquitoes are covered in scales, which are not found in many groups of insects. Scales are uniquely modified hairs and it's not clear what function they play on mosquitoes though they can be ornately colored and make mosquitoes very hard to spot when they're resting.

However, when I started researching mosquito scales, I discovered that all aspects of a mosquito's life history are fascinating so I wanted to share some of these tidbits even if it makes this newsletter longer than usual.

Let's start with some differences between males and females. Males have different mouthparts because they sip nectar from flowers rather than sucking blood, but even more noticeable, the male's antennae look like delicate feathers that are used to detect females.

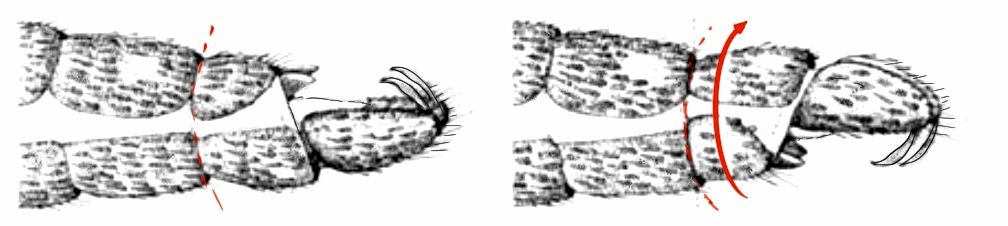

Furthermore, after emerging from water, the male's abdomen makes a unique 180 degree rotation over a period of 20 hours so the tip is upside-down (thus ensuring a perfect fit with the tip of the female's abdomen).

Males can locate females by the sound of their wings flapping 450-600 beats per second (you can mimic this with a tuning fork if you want to attract males), but they don't really need this because females will fly directly into groups of males as they swarm around vertebrates.

Mosquitoes can fly continuously for four hours and travel up to 7.5 miles in a single night, yet most of them stay within a few hundred yards of the waters where they hatch.

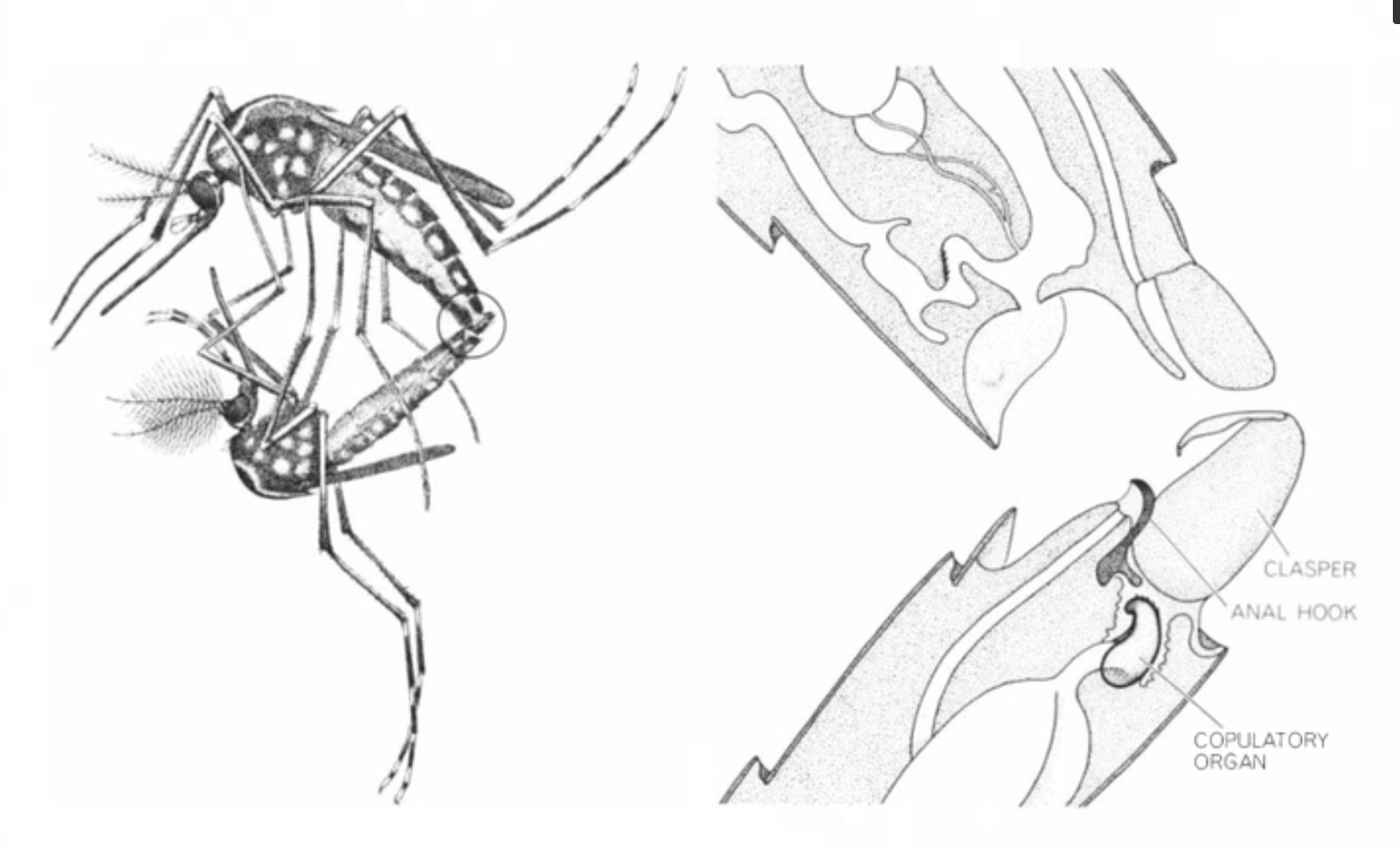

Mating occurs in flight as males land on a flying female's back then quickly flip upside-down under the female's belly to copulate, an act that can be completed in 15 seconds.

Like males, females also drink nectar, but they are the ones who suck blood because they need extra protein to create yolks for their eggs. They are first alerted to the presence of victims by the carbon dioxide gases we breathe out and other odors, then as they get closer they use their excellent eyesight to follow visual cues, and finally at close range they zero in on temperature signals.

Stabbing and sucking blood from a vastly larger critter is a dangerous undertaking, but females are cautious, skillful fliers. Like all members of the fly family, mosquitoes have halteres, a pair of wings reduced to club-shaped organs that whirl in circles like gyroscopes to enable extreme flying agility.

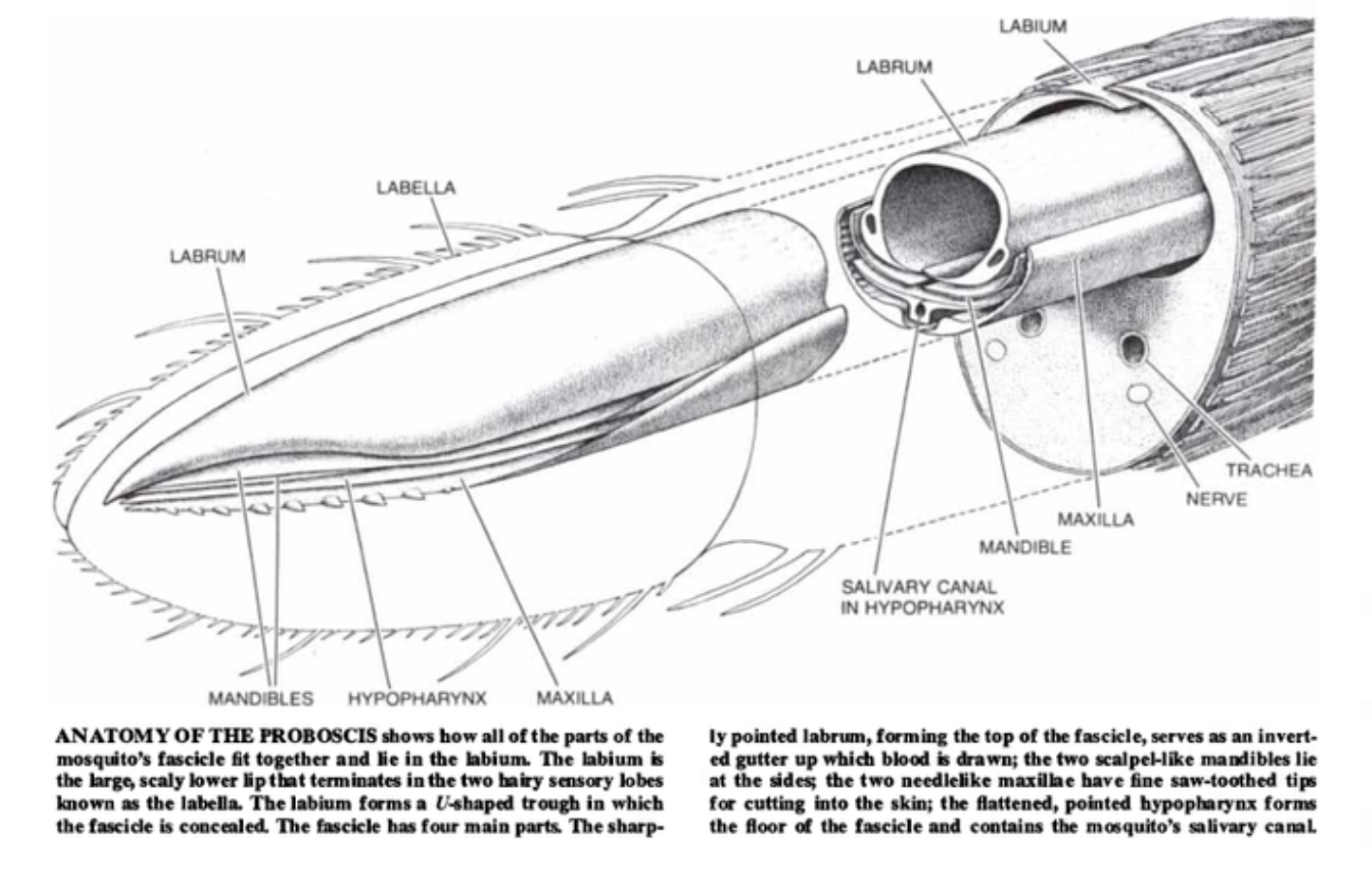

The piercing and sucking proboscis on a female mosquito is a complex, perfectly designed hypodermic needle. In fact, doctors are working on new models of needles based on mosquitoes because the design results in less tissue damage and pain.

To puncture the skin, mosquitoes use two maxilla with saw-toothed edges that take about 50 seconds to cut down into the skin. Some species inject saliva into the wound along with a cocktail of anti-coagulating substances to keep the blood flowing and this is where most mosquito-borne issues happen because viruses and protozoans ride the saliva into the wound.

As the female's abdomen expands with her meal of blood it puts pressure on a nerve cord running under her belly, which triggers her brain to start producing hormones that open hundreds of thousands of tiny pores on the eggs in her ovary. The eggs then soak up proteins from the blood to create yolks and expand enormously in size.

Females lay their eggs in a variety of water sources ranging from permanent lakes to tiny pockets of water trapped in cupped leaves. Some species lay eggs in elegant floating rafts, other lay eggs singly on surfaces above or in the water, and others lay eggs on their legs then dip their legs into water when they find a suitable spot.

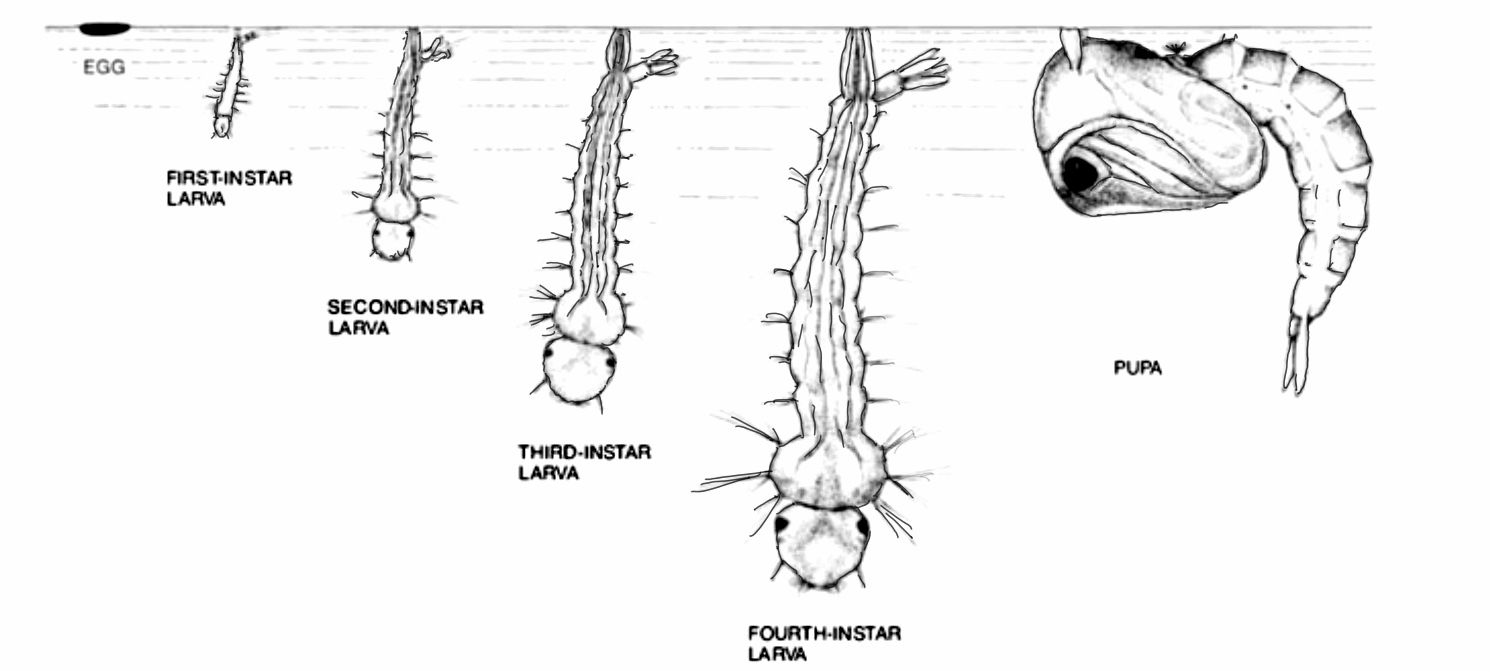

Because conditions can be so ephemeral, mosquito larval can go through their entire larval phase in 5-40 days. When hatching from the egg the larva pumps blood into its throat, causing its head to jerk abruptly so a spine on its head breaks open the eggshell allowing it to swim free.

Larvae grow rapidly on a diet of bacteria, algae, and organic matter that they sweep from the water with bundles of bristles around their mouths. You can already see adult legs, wings, and mouthparts forming under their skin, but they still need to spend several days resting in a comma-shaped pupal phase before emerging from the water as an adult to start their short lives of torment.

The next time you see a mosquito I hope you take at least a moment to consider the life of this marvelously successful creature.

Member discussion