What is a Fruit?

It's time to celebrate the late summer harvest because this is the season when farmer's markets are a cornucopia of goodness, and the branches of wild plants are hanging heavy with fruits and berries.

Like you, I thought I understood what a fruit was. It seems obvious what a fruit is if you hold one in your hand and take a bite of its juicy sweetness, but when one of my subscribers asked "what is a fruit?" I quickly discovered that I didn't know much at all.

The obvious way to answer this question is to describe what a fruit is. While the grocery store definition would include apples, oranges, grapes, bananas, etc., botanists more broadly define a fruit as the seed-bearing structure of any flowering plant.

This broader definition includes many items you might not expect, like tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, corn, bell peppers, eggplants, grains, and nuts. All of which develop from pollinated flowers and contain seeds.

Within this broader definition, fruit can be further categorized by how they present their seeds. For example, there are dehiscent fruits that split open to release their seeds, like pea pods, while indehiscent fruits that don't split open can be dry, like wheat kernels, or fleshy, like oranges and cucumbers.

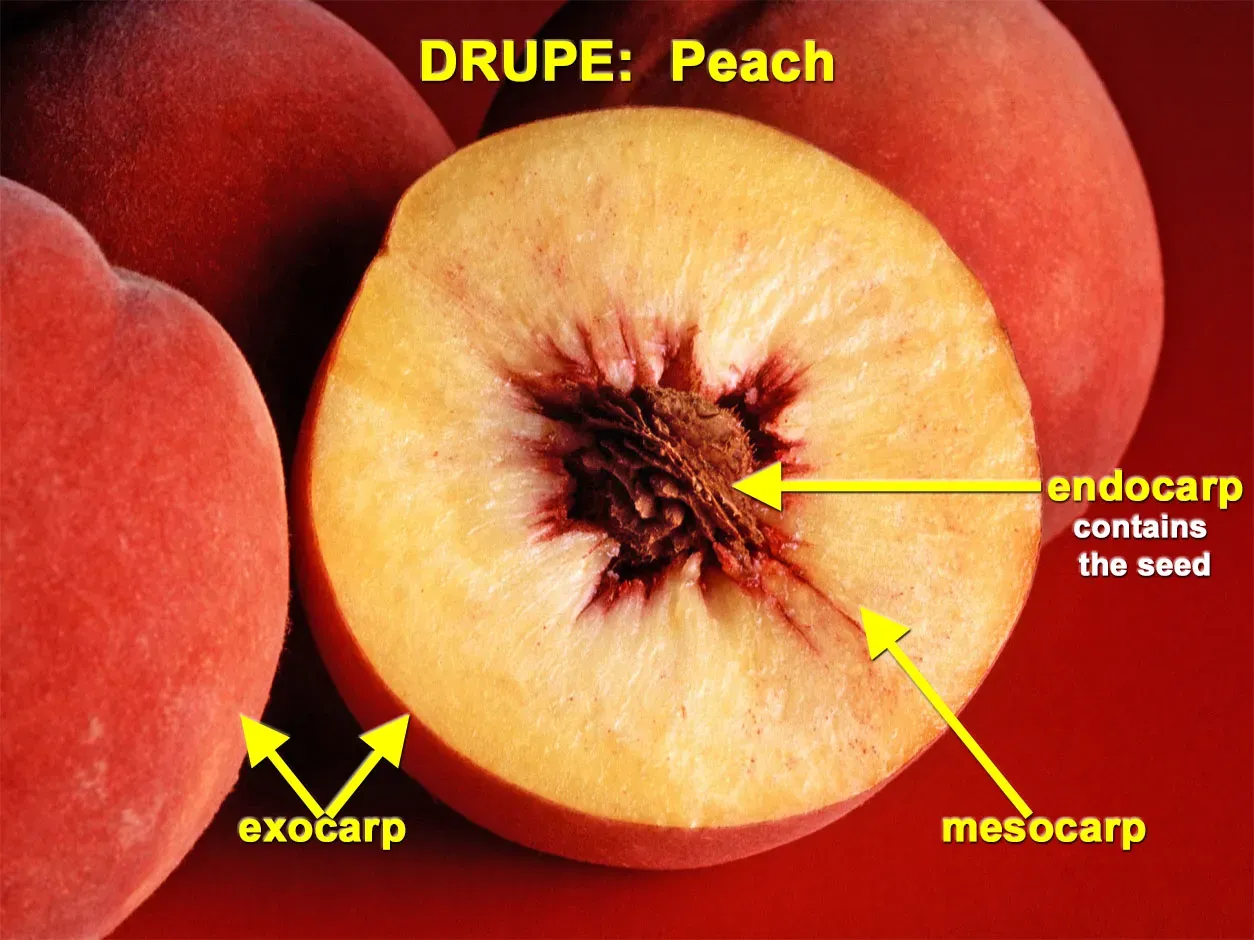

In all cases, the seed (or seeds) are enclosed and protected within an outer layer called the pericarp that is further divided into an exocarp, mesocarp, and endocarp. These outer layers are typically edible and brightly colored in order to attract animals that will eat the fruits and disperse the seeds to new locations. But in other cases, such as in grains and nuts, the pericarp is so reduced that you would hardly know it's there.

So that's part of the easy answer, but what I discovered is that fruits are far more complex than this because there's an inherent tension between hiding and protecting seeds while also providing them the resources they need to mature.

Producing seeds is an energy-intensive process and this energy is produced by respiration, which involves absorbing oxygen to burn sugars and starches while releasing carbon dioxide and energy.

Because their respiration rates are extremely high, and their protective outer layers limit gas exchange, seeds end up experiencing both hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) and an excessive buildup of carbon dioxide (due to the burning of stored energy). This imbalance plays a huge role in the ability of seeds to ripen, store energy, and then successfully germinate in the spring. In other words, it's a problem that has to be solved.

One part of the solution is that fruits, like leaves, are photosynthetic. In essense, fruits produce their own supplies of oxygen, which is critical because plants tend to produce fruits in mid- to late summer when their leaves are beginning to wither and break down. It's much easier to alleviate hypoxia in seeds when a fruit is producing its own supply of oxygen, rather than relying on the plant to deliver it.

Another part of the solution is that plants have evolved ways to recycle carbon dioxide that builds up inside seeds. After all, it makes sense to capture and reuse carbon produced inside a seed because seeds need to accumulate carbon to grow, not to mention stockpiling surplus carbon in the form of carbohydrates, proteins, or lipids in order to feed the future seedling.

Honestly, I don't fully understand the science behind this story and there are many more pieces than the simple equation I've outlined above. For instance, as fruits start to ripen they rapidly convert their photosynthetic chlorophyll into chromoplasts that accumulate high levels of carotenoids (which gives fruits the colors and smells they need to attract animals).

My intent is to simply convey that fruits are more amazing than you might realize, and these are the kinds of revelations that add a little bit of wonder to the world around us.

Member discussion