The Natural History of Clay

You may be familiar with clay from a pottery class, but if you think you know clay, it's time to think again.

Clays have been an integral part of the human experience from the very beginning. The Book of Genesis says, "The Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground," while the first human was named Adam, based on the Hebrew word adama, soil or clay. But the association goes much deeper than that, with clay being an essential ingredient in everything from the earliest known cookware to modern construction, industrial, and medical applications.

Clay is that moldable, sticky stuff that can be formed into vases, or that makes trails slippery when wet, but if you've never given clay a second glance, prepare to be amazed.

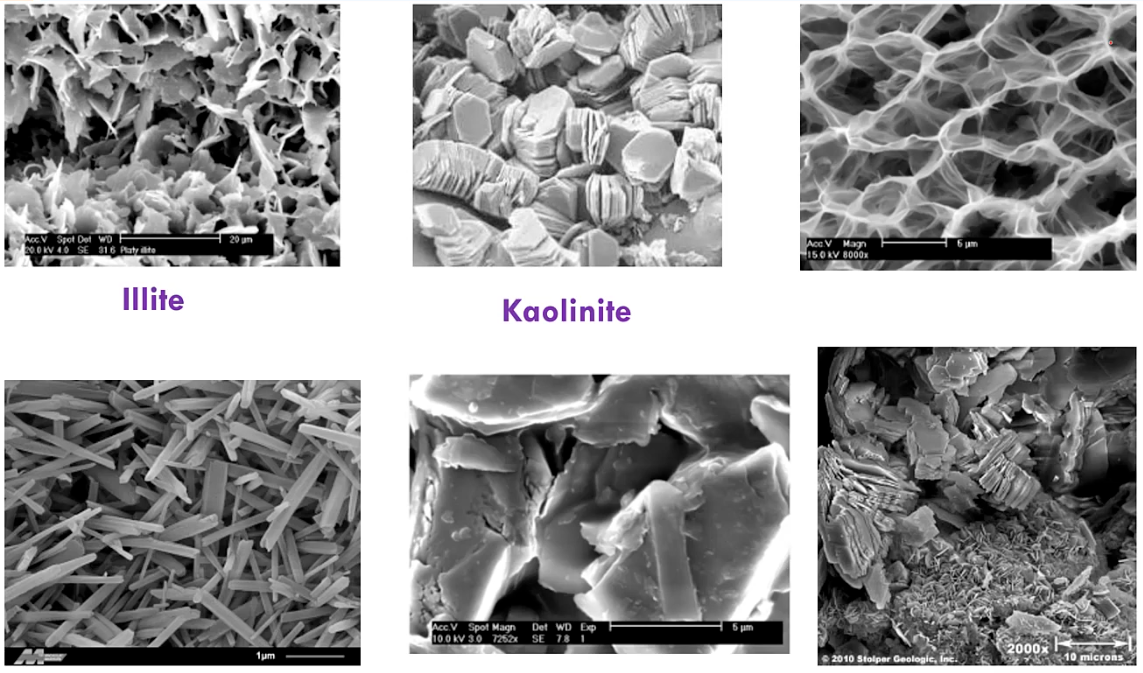

As rocks break down, they produce three types of particles known as sand, silt, and clay. Sand and silt are larger particles, but clay is in a class of its own. You could fit one million clay particles inside a single sand grain, so not only are clay particles impossibly small, but they also have unique properties not shared with sand and silt.

Sand and silt are inert materials, which means they are physically present but don't react with other materials. Clay particles, on the other hand, carry electrostatic charges and have a huge range of chemical and energetic interactions with the world around them. This gets a little complicated, but it's critical to understand what's going on here because the atomic structure of clays explains every part of why they matter.

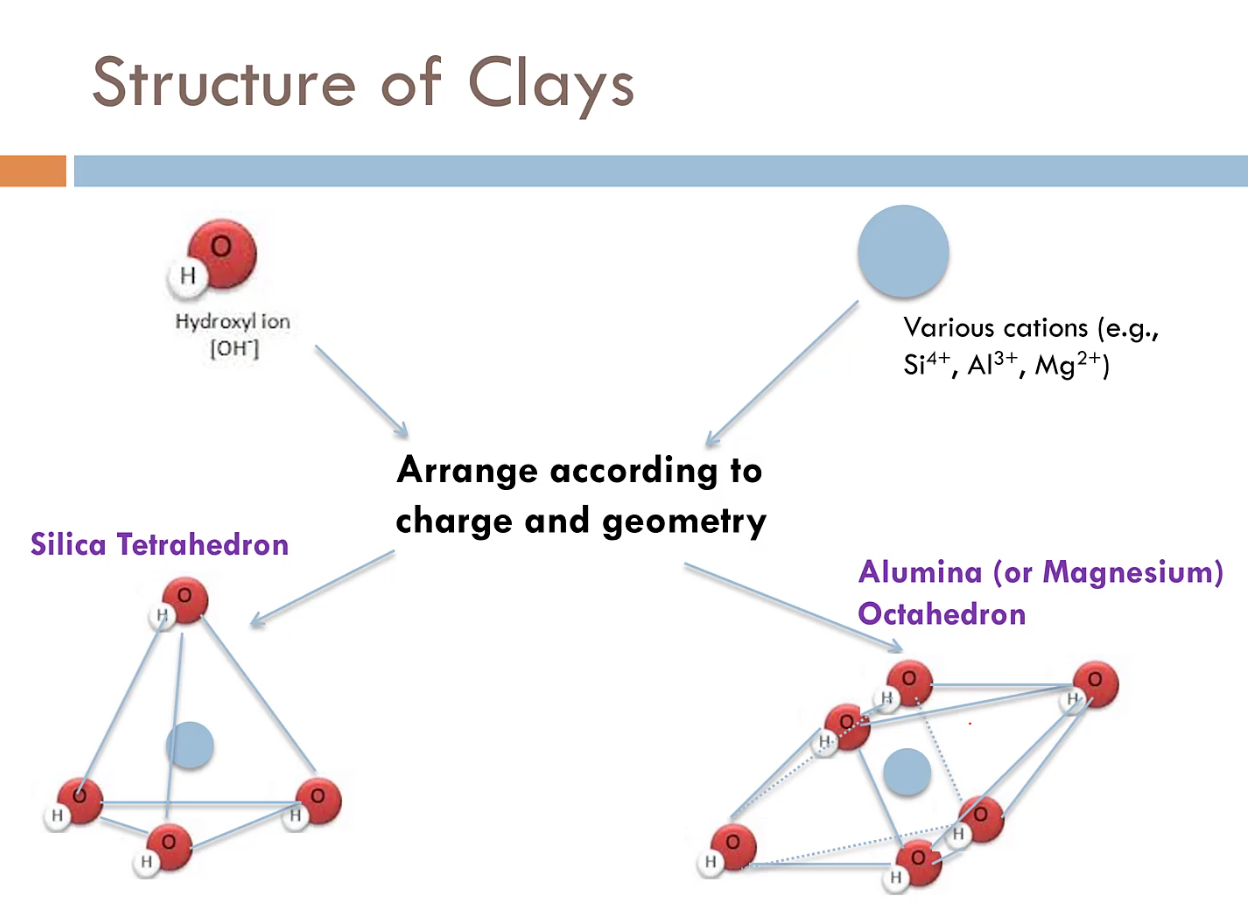

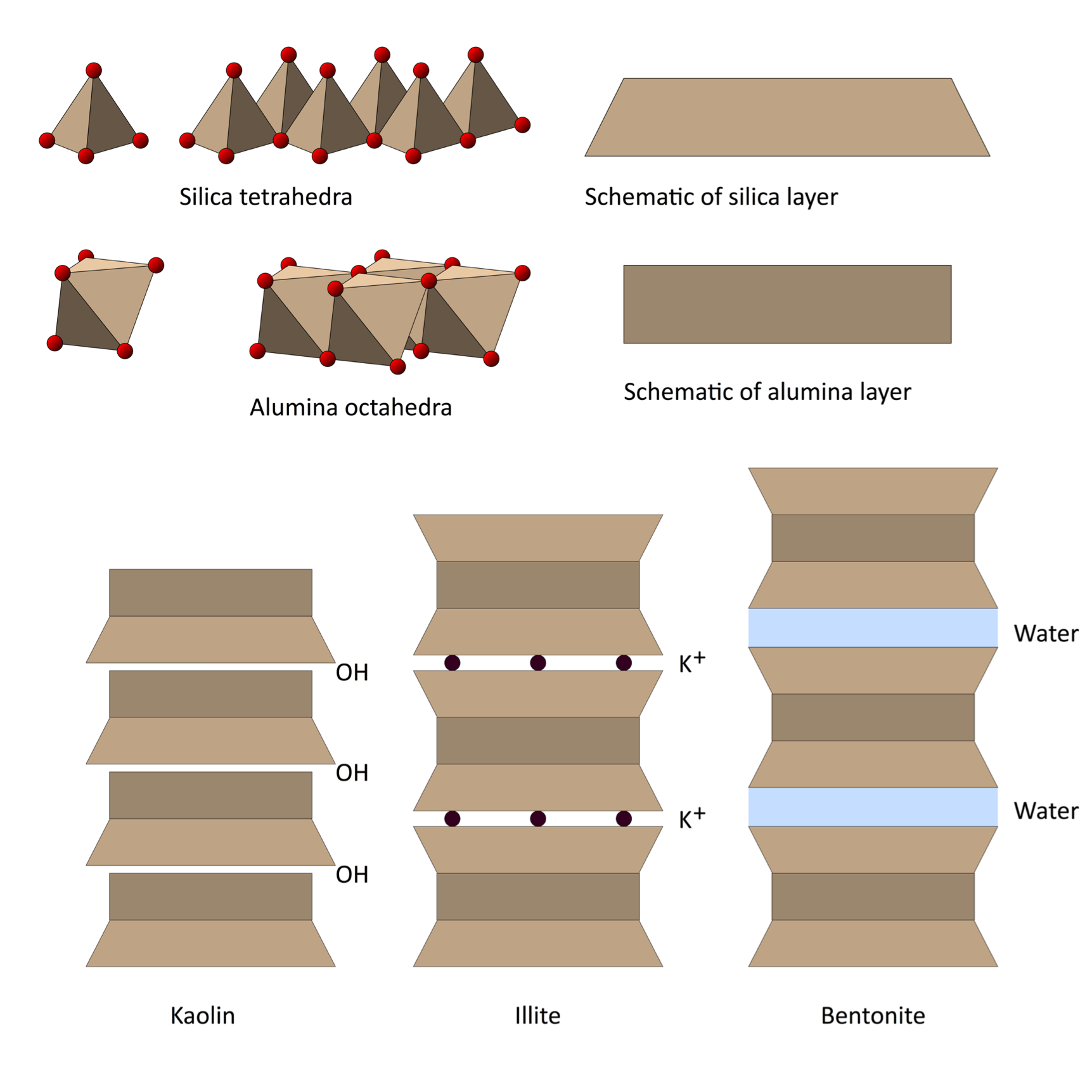

Clays are built from what are called hydroxyl ions, small chemical units comprised of one hydrogen atom and one oxygen atom that have a negative charge. These negatively charged ions then attract positively charged elements (cations) and arrange themselves into tetrahedrons or octahedrons based on which positively charged elements they attract.

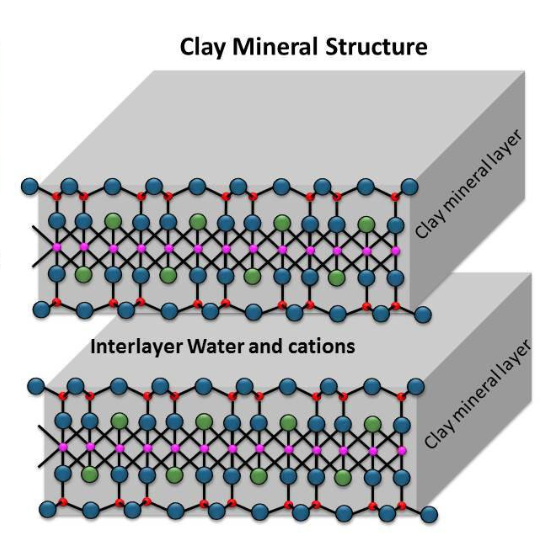

These tetrahedrons and octahedrons then link up into flat sheets that begin stacking like the pages of a book to form clay particles.

Depending on the bonds holding these layers together, the spaces between layers can either accept other positively charged cations or water molecules that make the layers slide past each other and give clay its unique slippery properties.

There are at least two key properties to keep in mind here. One is that every surface on these layers and particles is chemically and electrostatically interacting with the world around it. And we're talking an astronomical amount of surface area because clay particles are so small. A unit of clay the size of a sugar cube has as much surface area as a football field, and all of it is buzzing with the energy of life.

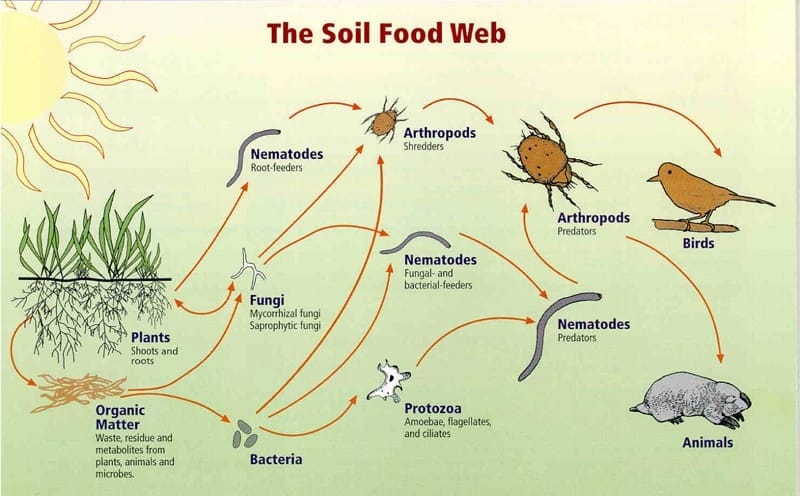

These buzzing surfaces are essentially living message boards, with clay particles storing and releasing chemical and energetic signals in response to the rapidly changing environment around them. In fact, one of clay's most important properties is called isomorphic substitution, which refers to its effortless ability to hold onto and swap out charged ions without altering its basic structure. In other words, clay can electrostatically grab onto and store mineral nutrients, then swap them out for other mineral nutrients, which makes clay the fundamental building block of soil food webs.

Without clay, vital nutrients would simply wash away in the rain, leaving behind sterile soil, but clay does much, much more than hold onto mineral nutrients. These electrostatically "sticky" surfaces also attract countless organic compounds, including amino and nucleic acids. And, together with bacteria and fungi, they begin gluing soil together into micro and macroaggregates that give soil its structure and life.

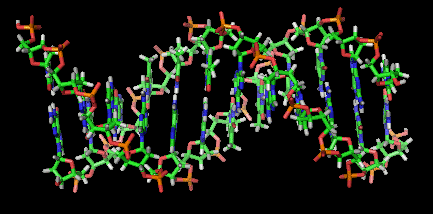

And this is where the story gets even weirder because there's a growing realization that these buzzing clay surfaces may be where life on Earth first started. Not only do clays attract amino and nucleic acids, but they also line them up in long chains that resemble DNA molecules and gene sequences. This proposed clay-DNA link is supported by the fact that amino and nucleic acids can even be physically incorporated into the structure of clay. Furthermore, clay surfaces are often highly convoluted (folded) in ways that optimize the organization of amino acids in the same way that DNA lines up in a double helix structure.

One idea is that this genetic material might have originally been an incidental byproduct of clay formation, but that some of these clay-gene assemblages could have been a better fit for their environment and grew to encode a greater amount of information until the clay component was weeded out of the equation. As one author recently noted, "clays are likely precursors to genes because [clays] spontaneously self-assemble, they self-replicate, and they would have been abundant on early Earth."

Circling back to Adam and the Book of Genesis, maybe there's a deeper wisdom behind this idea that life sprang from the dust of the Earth than we realize.

Further Reading:

Much of the literature on this topic is dense and technical but I got the best overview of the topic in this YouTube video by Dr. Kevin Franke ("Office Hours"). This presentation is an hour long and your attention might start drifting after the halfway point, but his explanation is clear and given in straightforward terms.

Here are two short and simply explanations on why clay is important in soil, and why clay is negatively charged.

The story of how clay builds micro and macroaggregates in soil is so important that I'll write a future newsletter on this topic, but if you have the stomach for it, this long and technical paper is a fascinating sneak peek at the topic.

Member discussion