Stone Cold Silent

Have you ever felt like the natural world is quieter than you remember it being? You're not going crazy; you might be noticing a global phenomenon with profound implications for all of us.

When I moved to the North Cascades five years ago, the first thing that caught my attention was an eerie silence everywhere I walked. I now spend my days hiking in nearly three million acres of wilderness, one of the biggest and most pristine places in the United States, but there are countless days when I feel lucky if I see (or hear) a single squirrel or bird.

This hasn't felt right to me because I imagine that a vast, healthy ecosystem should be brimming over with the sounds and activity of countless animals. Since I was new to this landscape, I started thinking this might be normal for the North Cascades, so when I decided to spend a month in the Sierra Nevada this summer, one of my goals was to compare how many animals and sounds I would find in a landscape that I know very, very well.

To my dismay, I was shocked to discover that Sierra Nevada forests and meadows weren't bursting with the sounds that I remembered from 15-20 years ago. The Sierra Nevada felt as silent as the North Cascades, and it left me terribly confused.

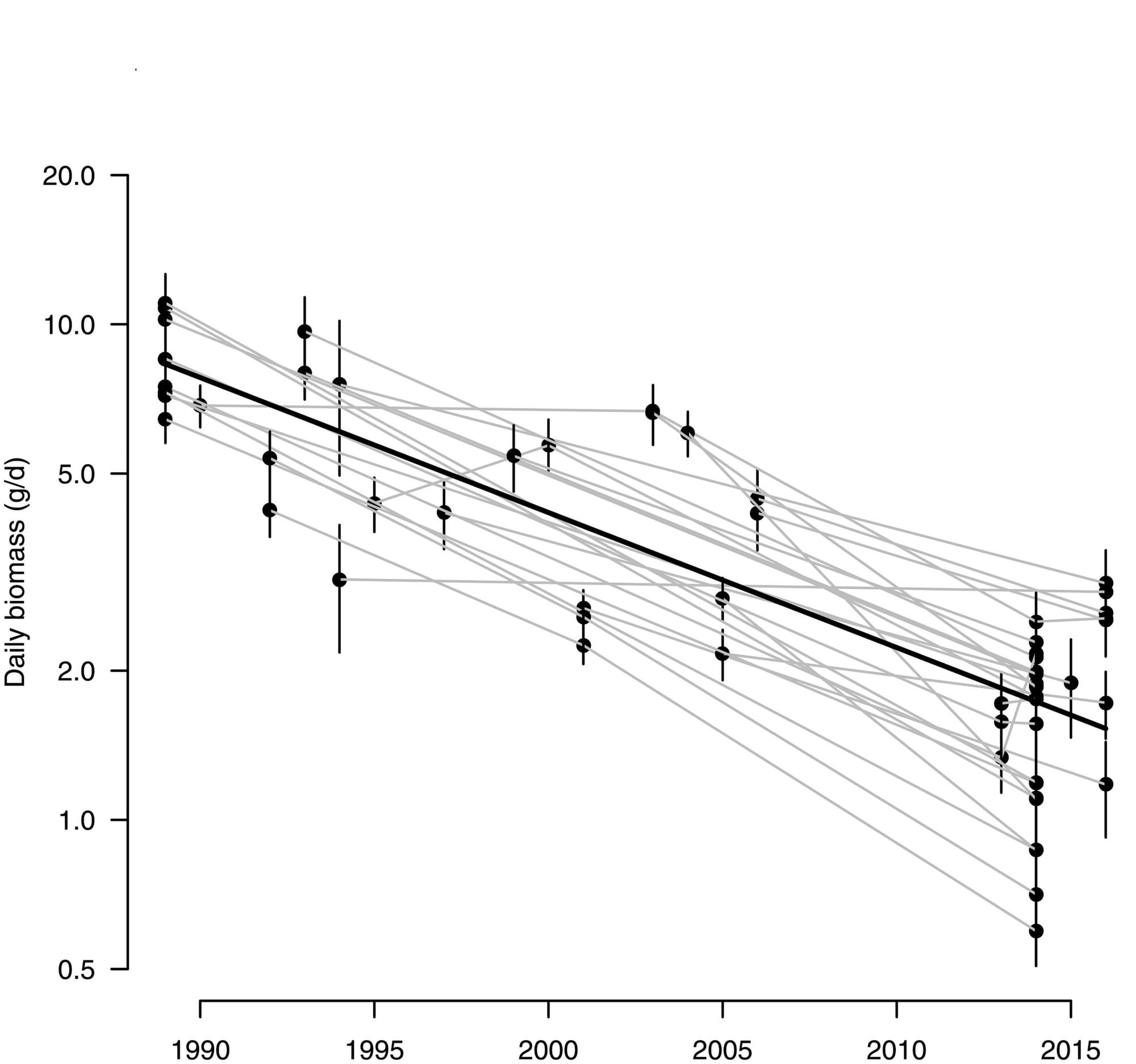

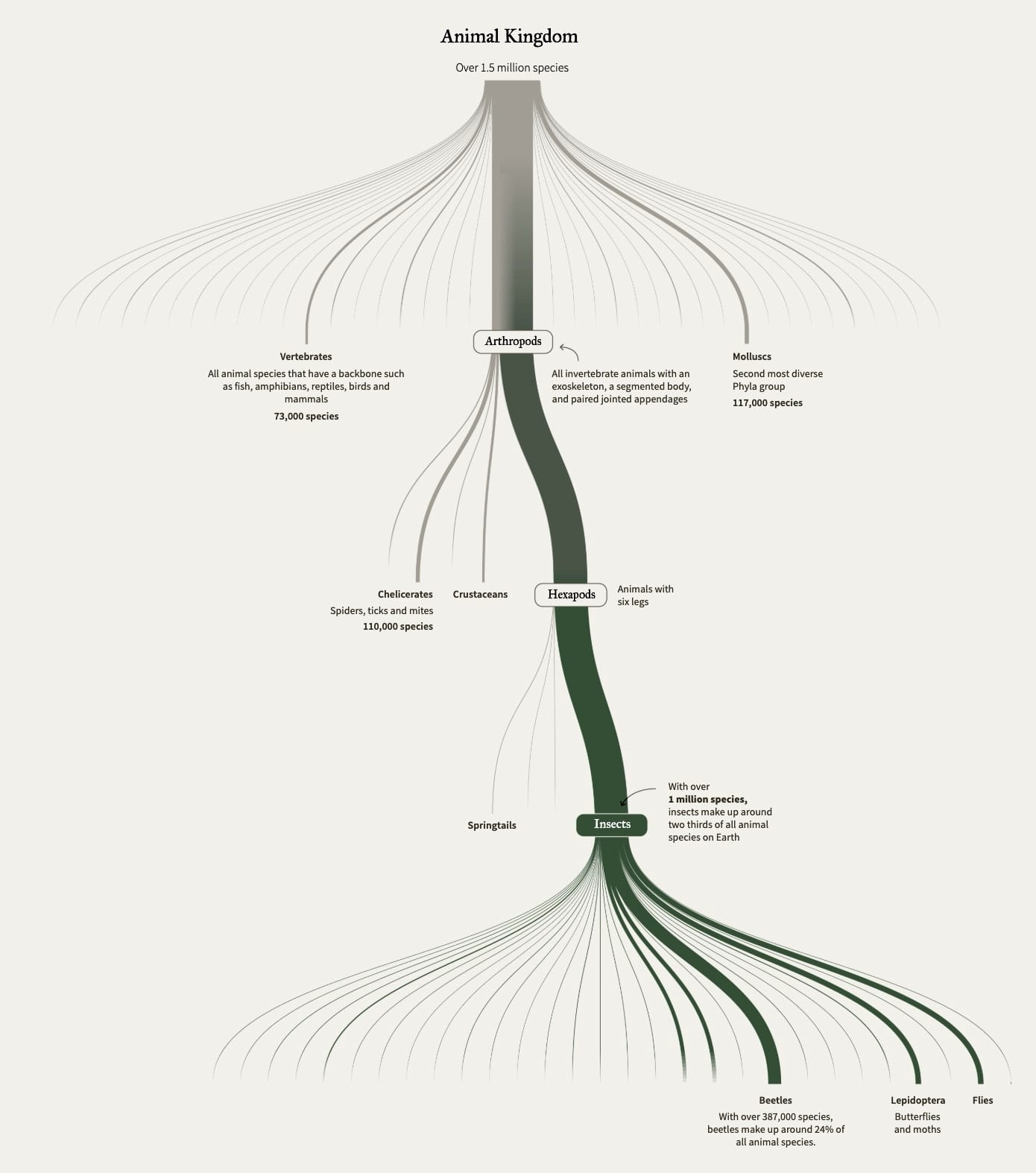

Then I read a news story about the collapse of insect populations, and I think I found the answer. It's now believed that insect numbers are declining at least 2% each year. This doesn't seem like much, but even if the number was 1% it means that we would lose one-third of the world's insects in 40 years, and scientists believe that the reality is far, far worse.

This seems like a trivial factoid until you realize that most living things are insects, so it's equivalent to losing one-third of the tree of life within decades. And when you lose insects, you lose the animals that depend on them. For example, the number of birds in North America has declined 30% since 1970, and the loss of insects is thought to be the leading cause.

When we lose buzzing insects, singing birds, and chattering squirrels the silent landscapes left behind are called acoustic fossils and this is happening all over the world. For example, nature recordist Bernie Krause estimates that over 70% of the soundscapes he's recorded on seven continents over the past 55 years have been lost. And a 2021 study that looked at 200,000 sites across North America and Europe found catastrophic declines in nature sounds across the board.

In this short YouTube interview, Bernie talks about a Sierra Nevada meadow that I know very well and how the soundscape changed after selective logging. (You can skip to 0:50 where he plays the recordings).

It turns out that humans are keenly tuned to the sounds of the natural world and that these soundscapes profoundly impact our emotional makeup, as well as cognitive abilities like attention spans, memory, problem-solving, decision-making, and creativity. So, what does it mean if we start losing these soundscapes?

Few people realize that human hearts and souls depend on natural soundscapes in ways that we're just beginning to understand. If our ears are sounding the alarm, maybe it's time we started listening.

Most of us have forgotten what the natural world sounds like in its full sonic splendor.

More resources:

Today's topic is closely related to the idea of shifting baselines.

And "dark diversity."

A subscriber just brought this new study to my attention.

Member discussion