Pollen Nation

Every year—without fail—plants start focusing on sex and blanketing the earth's surface with a material that's hard to miss.

Of course, we’re talking about pollen. It may be the bane of your existence, but it’s also a dominant feature of life on earth.

The problem for plants is that they are stationary and separate from each other. This makes sex, as an act of physical contact, impossible, but plants still manage to be phenomenally successful because they’ve found an extraordinary solution in the form of pollen.

Pollen grains are nothing more that microscopic packets of sperm cells. Some plants produce sticky pollen and use colorful flowers to attract pollinators such as birds, bats, and insects that fly around and carry pollen from the male structures of one plant to the female structures of another plant.

But a far more successful strategy is to produce extremely lightweight pollen that will be picked up by any breeze over six miles per hour and carried great distances. This is a highly inefficient strategy in terms of tiny pollen grains randomly hitting the right target, but wind-pollinated plants make up the difference by dumping immense quantities of pollen into the atmosphere.

It is estimated that wind-pollinated plants produce about 100 million grains of pollen per square yard.

As a result, much of the earth’s surface is dominated by wind pollinated plants which make up our grasslands and meadows, coniferous and deciduous forests. While only 10% of the world’s plant species are wind-pollinated, they account for 90% of all individual plants.

So that’s one part of the picture, but it’s also amazing to consider how pollen works on the microscopic level because it’s nothing short of a miracle.

Technically, the infinitesimally tiny pollen grain is a gametophyte—essentially it's an entire organism comprised of two cells whose sole job is to produce and deliver sperm. And surrounding this pollen grain is an important structure called the pollenkitt, an extremely tough and durable outer coat that can endure intense heat and cold, as well as strong acids and bases.

Even more important, the pollenkitt is composed of a diverse stew of proteins that are so specific to each species that the female structures on plants instantly recognize and reject pollen from the wrong species, and in many cases can even recognize and reject their own pollen so they don’t pollinate themselves.

When people have allergic reactions to pollen I always assumed it was because pollenkitts can be spiky and I thought that these spikes irritated our sinuses. It turns out that people have allergic reactions because the pollenkitts are composed of proteins and when you inhale pollen your body thinks you are being attacked by foreign organisms and launches an overzealous immune response.

The miracle of pollen is that in order to be successful it has to land on a tiny, sticky dot at the tip of the female structure in a flower.

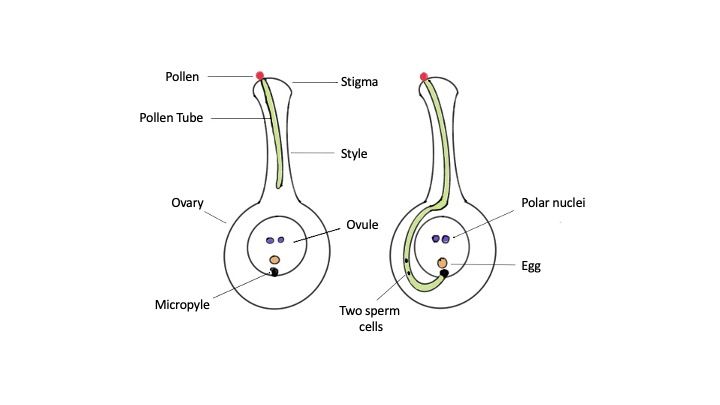

Once it lands on a sticky stigma, one cell of the pollen grain grows a pollen tube that extends into and down the length of the female style until it reaches a precise point on the ovule called the micropyle. Meanwhile, the other cell of the pollen grain subdivides into two sperm cells that are carried down the pollen tube and delivered to the ovule.

In flowering plants, seeds can only be produced if there’s a double fertilization. This means that while one sperm cell fertilizes the egg, the other sperm cell separately fertilizes two polar nuclei to form a nutrient packet (the endosperm) that will feed the growing egg. Together, the egg and endosperm form a seed.

I guess there are lots of ways to think about this miraculous process. On one hand, pollination is why we have life on earth, but on the other hand you might not be thrilled to hear that pollen counts are expected to increase 200% by the end of the century due to global warming. It's definitely a mixed bag.

Member discussion