Liquid Skeletons

Slugs, worms, and other lowly organisms may be primitive, but they embody one of the most successful body plans in the history of life on Earth.

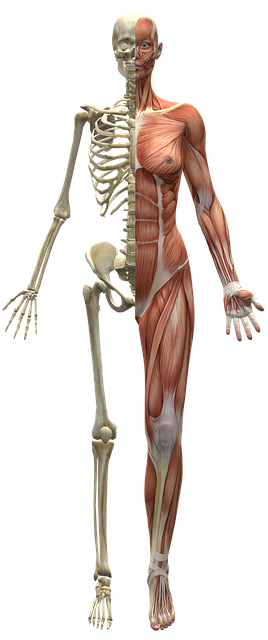

Because we are inclined to see the world through the lens of our mammalian existence, one of the tenets we take for granted is that animal bodies are built around bony skeletons. This bias is further confirmed because the vast majority of animals we see every day (including cats, dogs, horses, cows, birds, snakes, fish, and frogs) have bony skeletons.

Skeletons allow us to stand upright, and organisms without a skeleton would be little more than shapeless bags of tissue held together by an outer skin. Not only that, but skeletons play a critical role by providing attachment points that muscles can push and pull against, allowing organisms to perform complex actions such as moving through the world in search of food, shelter, and mates.

But our mammalian bias blinds us to a glaring reality: the majority of animals on Earth, not to mention plants, rely on a completely different body plan known as a hydrostatic skeleton, and these skeletons offer many unique advantages over bony skeletons.

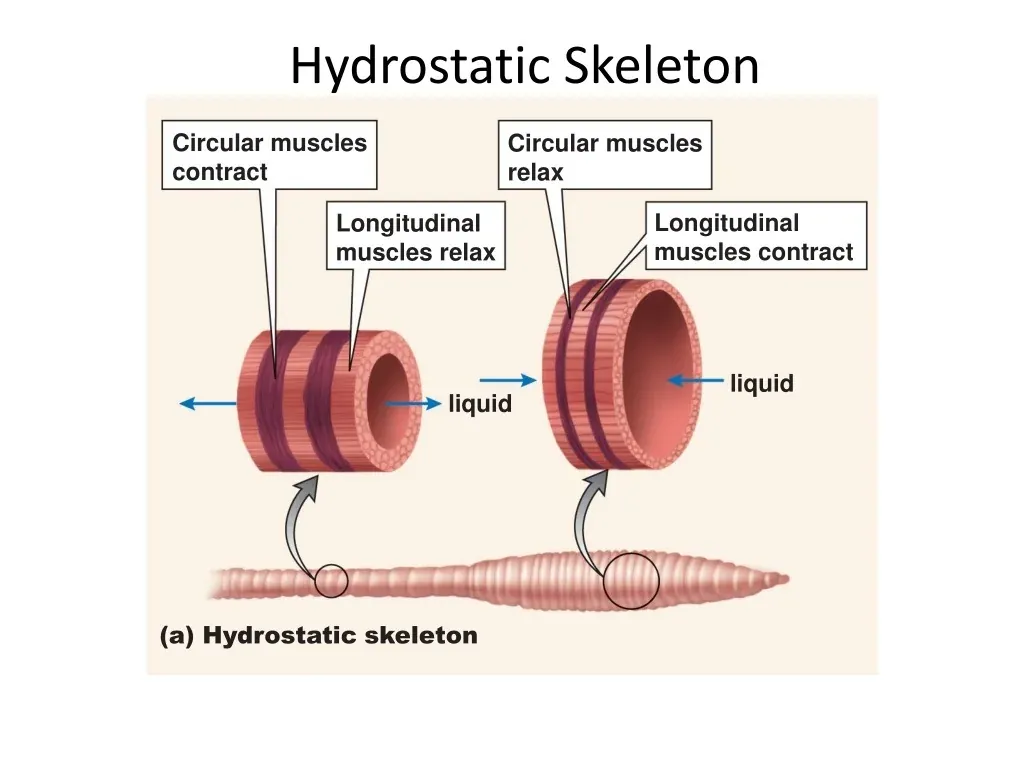

Hydrostatic skeletons consist of a water-filled cavity, and when you apply force to this cavity, it changes shape because water is not compressible (imagine putting water in a balloon and squeezing it). In essence, this water-filled cavity becomes a sturdy structure that physical forces can then push and pull against. In the case of plants, force is created through osmotic pressure, and in the case of animals, force is created by muscles in the wall of the cavity.

Organisms with hydrostatic skeletons are generally cylindrical in shape, with antagonistic forces being applied longitudinally along the cylinder's length or circularly around the cylinder's circumference. Think of how an earthworm moves, with lengthwise muscles pulling its body shorter while its circumference expands, then its body narrows as circular muscles squeeze its body, and it stretches out lengthwise again.

How an earthworm moves. Video from Storyblocks

Advantages of hydrostatic skeletons include the fact that bones are brittle and difficult to build and repair because bones are made from calcium, which is a scarce nutrient in nature (and almost completely lacking in some environments). On the other hand, hydrostatic skeletons are comparatively easy to heal at minimal cost because you only need to repair the cavity and fill it with water again.

Another advantage of hydrostatic skeletons is that they are lightweight and flexible, allowing efficient movement with little muscle mass. For this reason, animals with hydrostatic skeletons move easily and can squeeze through oddly shaped openings while swimming or burrowing.

Its easy to visualize the basic function of a hydrostatic skeleton in a worm, but it's astonishing how widespread these types of hydraulic mechanisms are in the natural world. Not only are hydrostatic skeletons found in slugs, sea anemones, sea stars, jellyfish, and squids and octopuses, but they are also found in the immature stages of insects, and in animals like crabs during the stages when they shed their hard shells and are growing new shells again.

Hydrostatic skeletons are hidden everywhere, for example, spiders move their legs using hydrostatic skeletons, while mammalian penises are blood-filled hydrostatic skeletons. And this doesn't even count the modified hydrostatic skeletons known as muscular hydrostats, which are hydrostatic skeletons that fill their cavities with muscles rather than water, but rely on the same principles. Muscular hydrostats include tongues, elephant trunks, and the snouts of animals like anteaters and manatees.

While bony skeletons are common and offer a range of significant mechanical advantages, it's incredible how many of the world's plants and animals rely instead on hydrostatic skeletons.

Further reading:

For a general introduction it's worth reading about hydrostatic skeletons on Wikipedia, and this longer and more technical scientific paper is a great overview of the topic.

Today's newsletter is inspired by a fascinating online course I'm taking with tracking and wildlife expert David Moskowitz and Nyn Tomkins. This two-part course covers the framework of animal skeletons and how skeletal structures shape the form and function of mammals. It's a very detailed course, but the coverage is generous and clear, with a focus on paying attention and fostering deeper connections with animals. I'm currently watching the recorded lessons from Part One and learning a ton, and I'm even more excited that Part Two will be coming out very soon. If you're an artist or naturalist looking to learn more about the structure of mammals, this course is highly recommended.

Member discussion