Layered Toxicity

Pikas are best known as icons for climate change, but the story of how they survive harsh mountain conditions is more complicated than you realize.

If you've hiked anywhere in the rocky landscapes of western mountains you've almost certainly heard the loud, sharp calls of pikas warning each other of your presence. Cryptically hidden and scampering amid rock crevices, these lovely little rabbit relatives that look like guinea pigs can be very hard to see.

To my utter amazement, I had the great fortune this week of sitting within a few feet of two pikas (one larger male and one smaller female) who went about their business as if I wasn't there. I'm used to seeing pikas warily watching the world with big beady eyes and darting quickly into hiding places, so I was unprepared to discover how relaxed they can be.

Over the course of several hours, these two pikas spent long periods of time drowsing in the warm sun, grooming, eating their fecal pellets (a common rabbit behavior), yawning, and stretching.

Such languid moments are rarely observed because a pika's life is otherwise a blur of frenetic energy as it spends its entire spring and summer squabbling over territories, seeking mates, and raising babies.

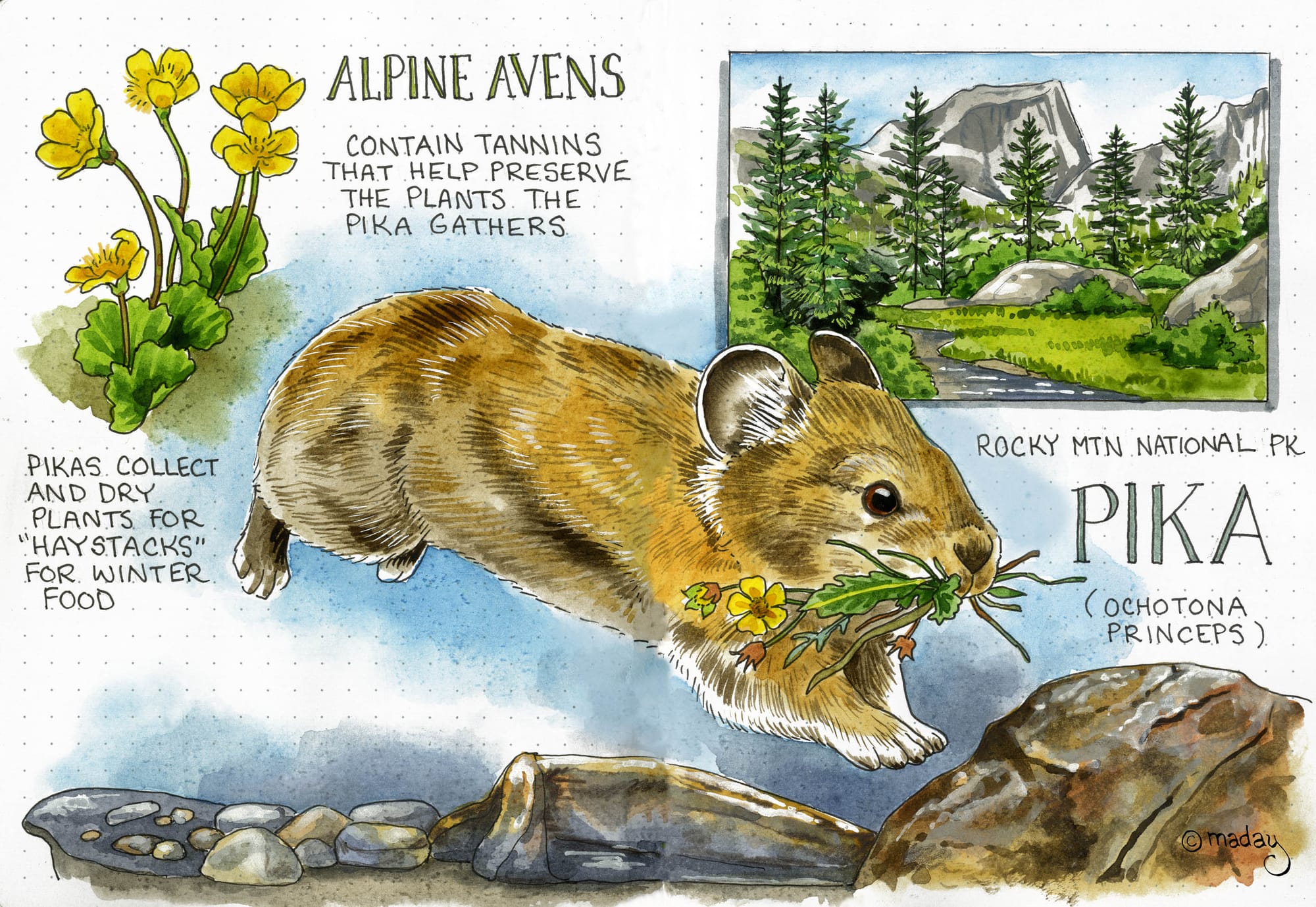

At the same time, pikas must gather enough surplus food to get them through the winter. Pika's don't hibernate and they don't accumulate fat, so they spend their summer harvesting, drying, and storing up to 50 pounds of food in a "haypile" that is literally the centerpiece of a pika's life.

Gathering this much surplus food in a rocky mountain landscape takes a tremendous amount of time and effort, and surpisingly, it also takes a lot of careful planning.

While some plants grow quickly and don't protect themselves, other plants invest much of their energy into protecting themselves with toxic, hard-to-manufacture compounds like phenolics and sesquiterpenes. These compounds are an effective defense for plants because they inhibit digestion, so herbivores avoid these plants.

Here's where things get interesting: Pikas spend the summer eating yummy (i.e. unprotected) plants, but when it comes time to harvest plants for the winter they gather both yummy and toxic plants, then carefully layer them in their haypiles.

It turns out that toxic plants (by which I mean plants protected by secondary compounds) have two interesting properties that benefit pikas. One property is that toxicity breaks down over time, so that by mid-winter these toxic plants are as yummy and nutritious as summer (unprotected) plants. The other trait is that phenolics and other secondary compounds have anti-fungal and anti-bacterial properties, so they act as preservatives when layered generously throughout a slowly decomposing haypile.

One other fascinating part of this story is that a pika will typically store 350 days worth of food in its haypile but only eat 180 days worth of food over the course of a winter. It doesn't make sense that a pika would spend so much time gathering food it doesn't eat, but it turns out these unused haypiles decompose into patches of highly fertile soil, and plants that grow on these soils produce higher levels of nitrogen. This might benefit a pika in its lifetime, or it might benefit closely related offspring that take over a pika's territory after it dies, so it seems like a worthwhile payoff for all that effort.

Member discussion