Ice Nucleating Bacteria

You might think that ice simply forms when temperatures drop below freezing, but things are never so simple in nature, and there's an unexpected piece to this story.

Everyone knows that when temperatures drop below freezing, water turns into ice. You can easily watch this happen in mudpuddles, ponds, or ice cubes in your freezer. What you may not realize, however, is that freezing is actually a carefully orchestrated dance of water molecules reorganizing into an intricate latticework of ice crystals.

At most temperatures below freezing, this complex reorganization of water molecules requires still, stable conditions (which is why puddles and ice cubes freeze so easily). But as soon as you introduce turbulence to the mix, like in a river, then water must get very, very cold (as low as -40 to -50℉) before spontaneous ice formation can overcome the hurdles imposed by turbulence.

Now, let's shift our focus upwards and ask a simple question. How in the heck do clouds produce snow (and snow that melts into rain as it falls) if they're constantly turbulent? It turns out that this is a critical question, and the answer says a lot about how all life on Earth has evolved over the past 2.3 billion years.

Water is constantly evaporating off the Earth's surface (both land and ocean) and rising into the atmosphere as vapor. But vapor is a gas that would remain airborne indefinitely unless it can be converted back to a liquid or solid that has physical weight and can fall.

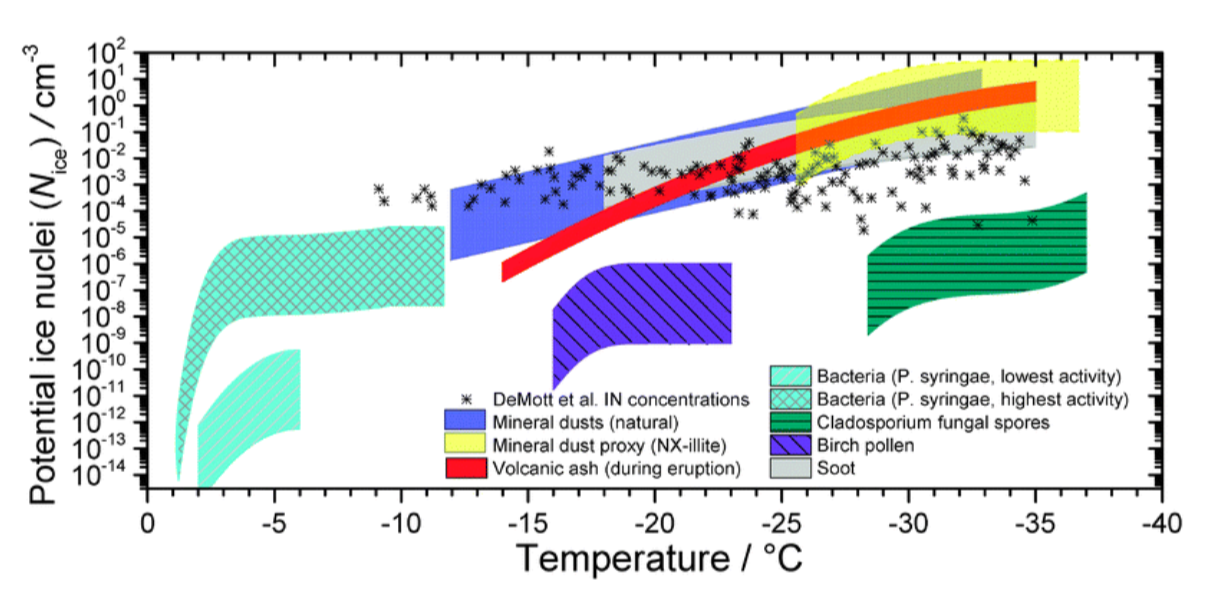

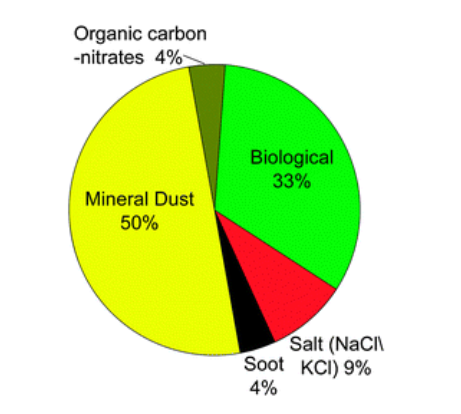

Fortunately for life on Earth, water vapor readily converts into liquids and solids through a process called condensation, which occurs when temperatures drop below the dew point. However, condensation first requires condensation nuclei in the form of airborne particles that include pollen, spores, dust, clay, soot, and human emissions.

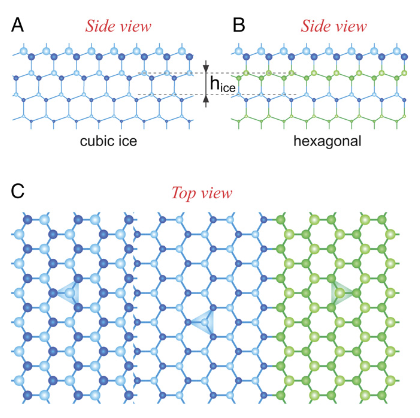

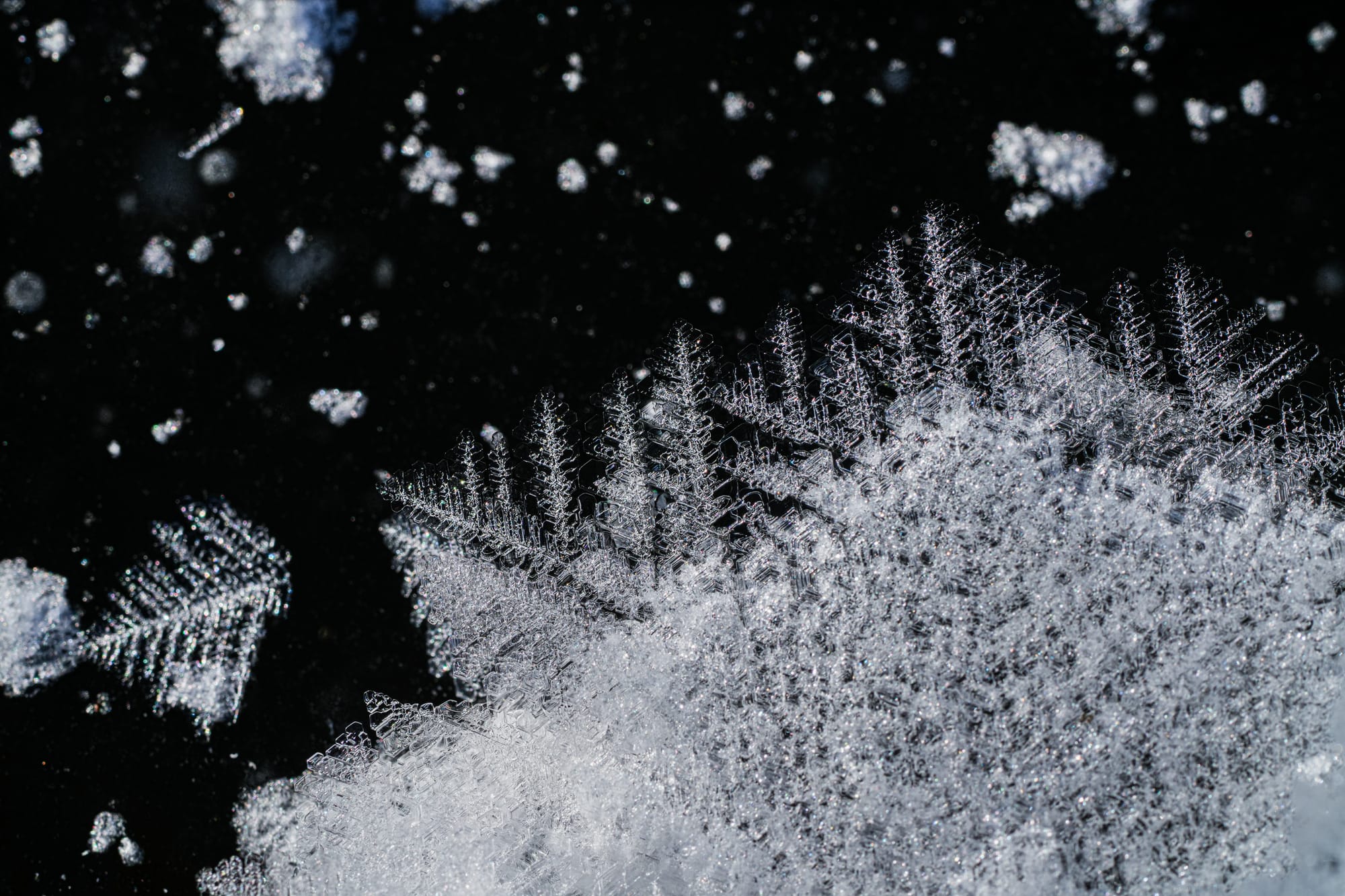

At low temperatures, water vapor attaches to one of these particles and turns into ice crystals. These crystals then continue to grow (in the complex latticework mentioned above) until they're heavy enough to fall as a snowflake. If the air is cold enough, a snowflake might fall all the way to the ground or melt into a raindrop as it travels through warmer layers of air.

The problem is that building these delicate crystal latticeworks requires either extremely cold temperatures or stable air, and neither condition is common in the atmosphere. This is where ice nucleating bacteria enter the picture.

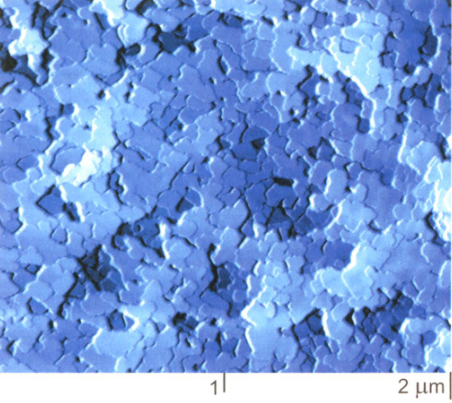

It turns out that some species of bacteria, as well as some fungi and algae, can create ice at remarkably warm temperatures. The universally abundant bacteria Psuedomonas syringae, which are by far the best known and the best studied of this group, promote ice formation by embedding large protein molecules on the surface of their cell membranes.

These proteins have the exact shape to grab water molecules and start stacking them in the latticework structures that promote ice formation through epitaxial growth. This nudge is so critical that it can instantly create ice crystals, even in turbulent conditions and at temperatures just below freezing, where freezing would otherwise be impossible.

The classic demonstration of how ice forms instantly in a jar of supercooled water when Pseudomonas syringae is added.

What's remarkable is that the crystallization of ice doesn't occur easily on airborne particles because most particles have irregular shapes that don't mirror the geometry of nascent ice crystals. This means that a very significant, but still unknown, portion of the Earth's rain and snowfall is created by bacteria and other ice nucleating agents.

This is already a long newsletter, but I'm imagining you're wondering why bacteria produces ice, and this is where the story gets really interesting. Plant leaves are one of the largest surfaces on Earth, and 1-10 million bacteria live on every leaf, with Pseudomonas syringae being one of the most abundant and widespread species in the world. Life on a leaf surface, however, is extremely challenging.

Bacteria would starve to death because leaves protect their nutrients with tough and impenetrable cell membranes, so bacteria need a way to access these nutrients, and they have found an astonishing solution. Bacteria have evolved the ability to create ice because ice crystals cause cell membranes to rupture and release hidden nutrients. Gardeners, farmers, and horticulturalists know this phenomenon as "frost damage."

So that's one part of the story. The other part of the story is that immense numbers of these bacteria are constantly being lifted off leaf surfaces and carried into the atmosphere through wind and evaporation. These microscopic organisms would be trapped forever in the atmosphere except that their ability to serve as condensation nuclei and create snowflakes ensures that they are carried back to the Earth's surface every time it rains or snows. In other words, we can thank bacteria for the life-giving rain and snow that sustains life on Earth!

Additional Reading:

As you can imagine, many papers have been published on this topic since it was first proposed in the 1960s.

In particular, I'm fascinated by the idea of the bioprecipitation feedback loop.

This paper is pretty technical in the middle sections, but still provides a lot of great information. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of Pseudomonas syringae, but diverts to other topics later in the paper.

Member discussion