Hidden Hitchhikers

Over the past couple weeks I've spent a lot of time hiking through fields of flowers in high mountain meadows, and among the countless bees and butterflies there have been lots of hummingbirds.

You can easily find hummingbirds in high mountain meadows, and this is especially true in mid- to late summer when hummingbirds use these flower gardens as stepping stones to fuel their long southbound migrations.

But under the surface of their high-energy flights between flowers there is another story taking place, and this story involves hidden hitchhikers.

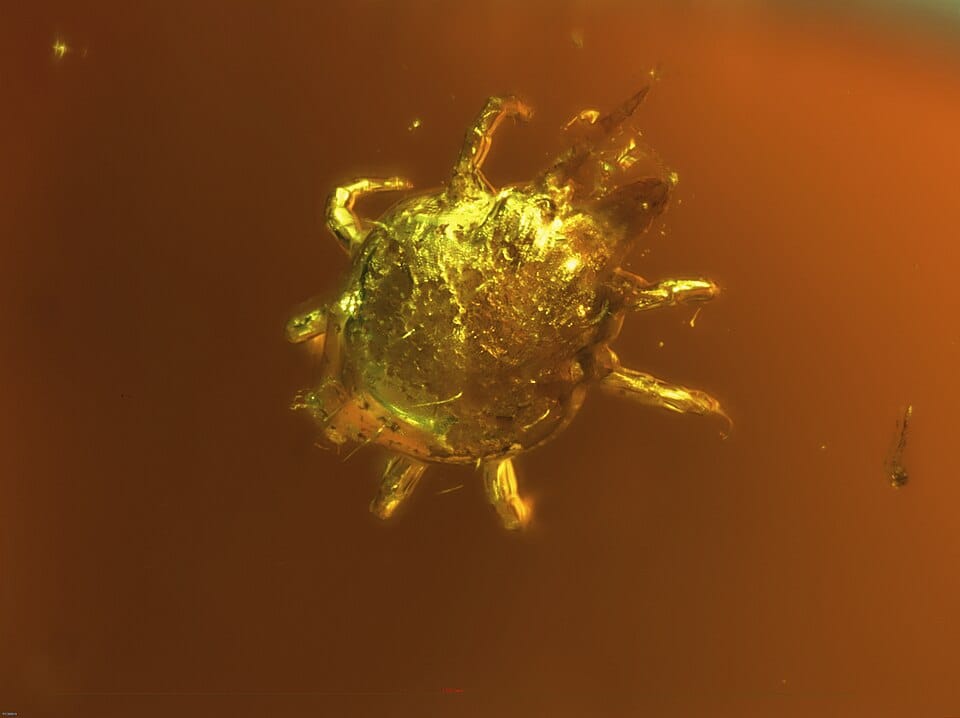

I'm sure you've heard of mites, but did you know that mites are literally everywhere?! These extremely small relatives of spiders, scorpions, and ticks first evolved over 500 million years ago and have since become the most diverse and successful invertebrates in the world.

It is thought that there are 3-5 million types of mites in the world, and probably many more. For example, scientists have documented over 100,000 mites of more than 150 species in a single square yard of dead leaves and soil on the forest floor, and mites have been found on every animal and in every niche possible.

One group of mites are called flower mites, and they specialize on living in flowers, where they eat nectar and pollen. Flower mites can have a significant impact on flowers because they might consume 40-50% of the nectar that a flower produces, affecting the flower's fitness and ability to attract pollinators.

This works out great for flower mites, except that at some point they run out of nectar supplies and mating opportunities, but they're so small they can't easily walk to new flowers or new plants.

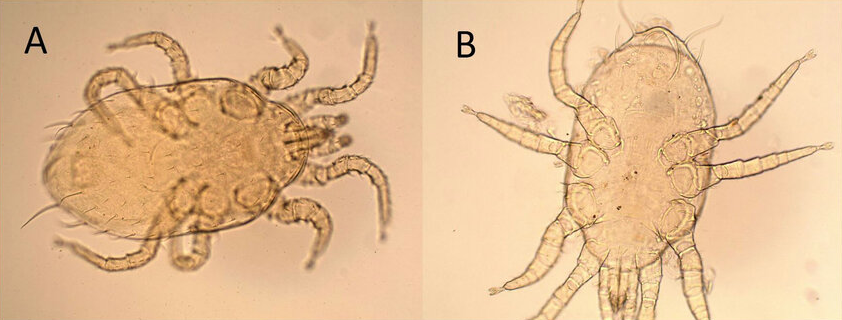

Therefore, flower mites take advantage of visiting pollinators to hitch rides to new flowers, and each type of mite has evolved to hitch a ride on a specific kind of pollinator ranging from beetles, to butterflies, to bats, to hummingbirds.

These choices matter because mites need to end up on new flowers of the same species, so "getting on the wrong bus" means almost-certain death. This is especially problematic for the flower mites that hitch rides on fast-moving hummingbirds.

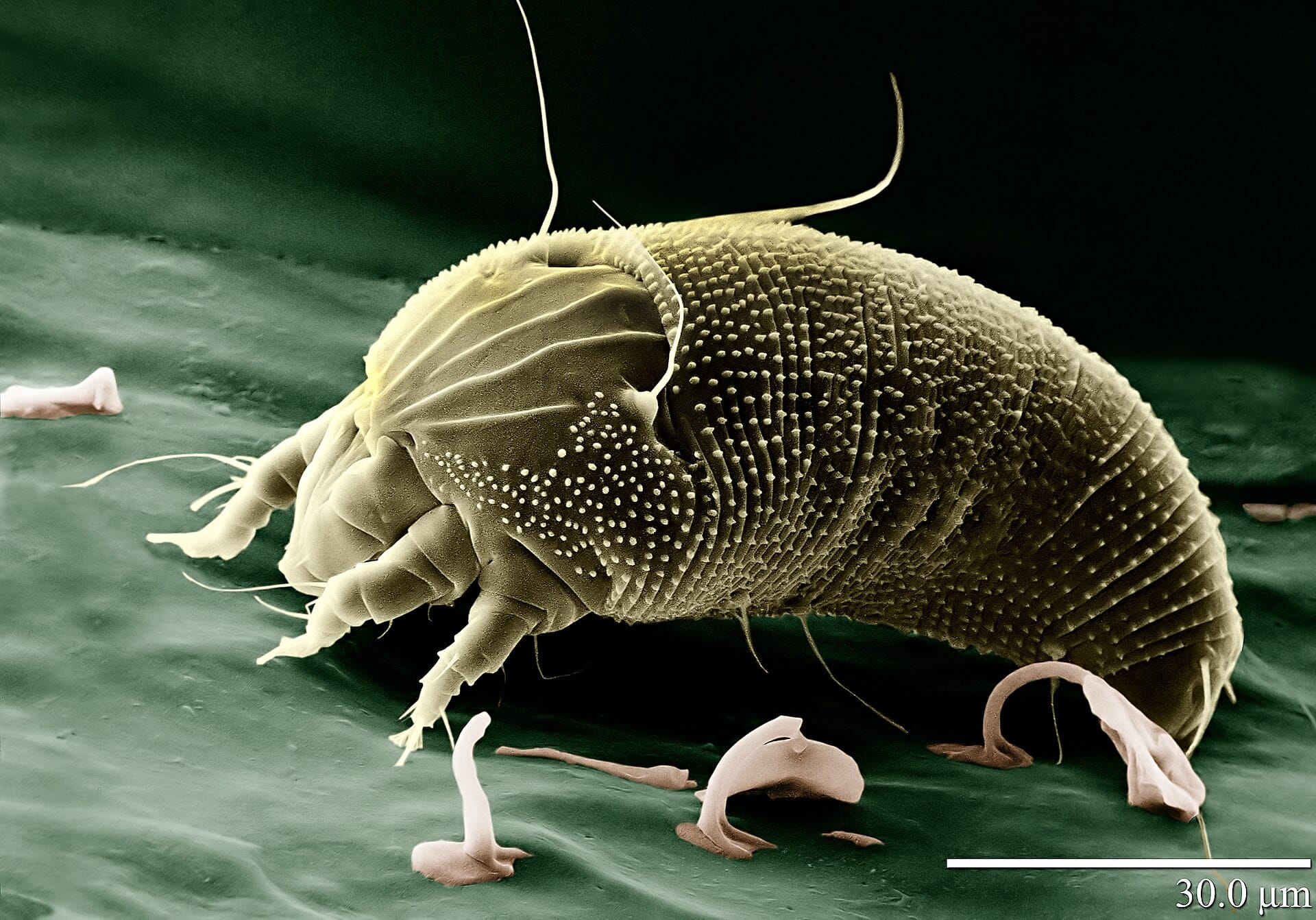

Hummingbird flower mites must instantly judge whether a fleeting hummingbird is visiting the kinds of flowers the mite needs, and then must get onto the hummingbird's bill and secure a safe foothold—all within milliseconds!

New research is showing that there's a lot going on here. First, the mite must smell the scent of other flowers on the hummingbird's bill and evaluate whether the bird is going where the mite needs to go. Then the mite uses the electrostatic charges generated by the high frequency flapping of the hummingbird's wings to "leap" onto the bird's bill. Then the mite must run faster, relative to its size, than a cheetah to reach a safe hiding place in the bird's nostrils before the hummingbird zooms off again.

Video depicting how mites use the electrostatic charge on a hummingbird bill to "leap" onto the bill.

When the hummingbird arrives at a new flower the mite reverses course by deciding whether to jump off, and then running from the nostril, down the bill, and onto the flower before the hummingbird moves on, as seen in the video below.

Footage of mites on a hummingbird's bill.

I imagine it must be a nuisance to have mites running in and out of your nostrils all the time. Fortunately, these tiny hitchhikers don't directly harm hummingbirds, but they do impact hummingbirds by competing for the same limited nectar supplies. It's not a great way of saying thank you for the free ride you've just gotten!

Member discussion