Here They Come!

You read about this all the time: visitors to a national park get too close to animals in search of photos, and then get hurt. However, in a situation last week where it seemed like angry bighorn sheep were confronting visitors in Jasper National Park, I had a different theory about what was happening.

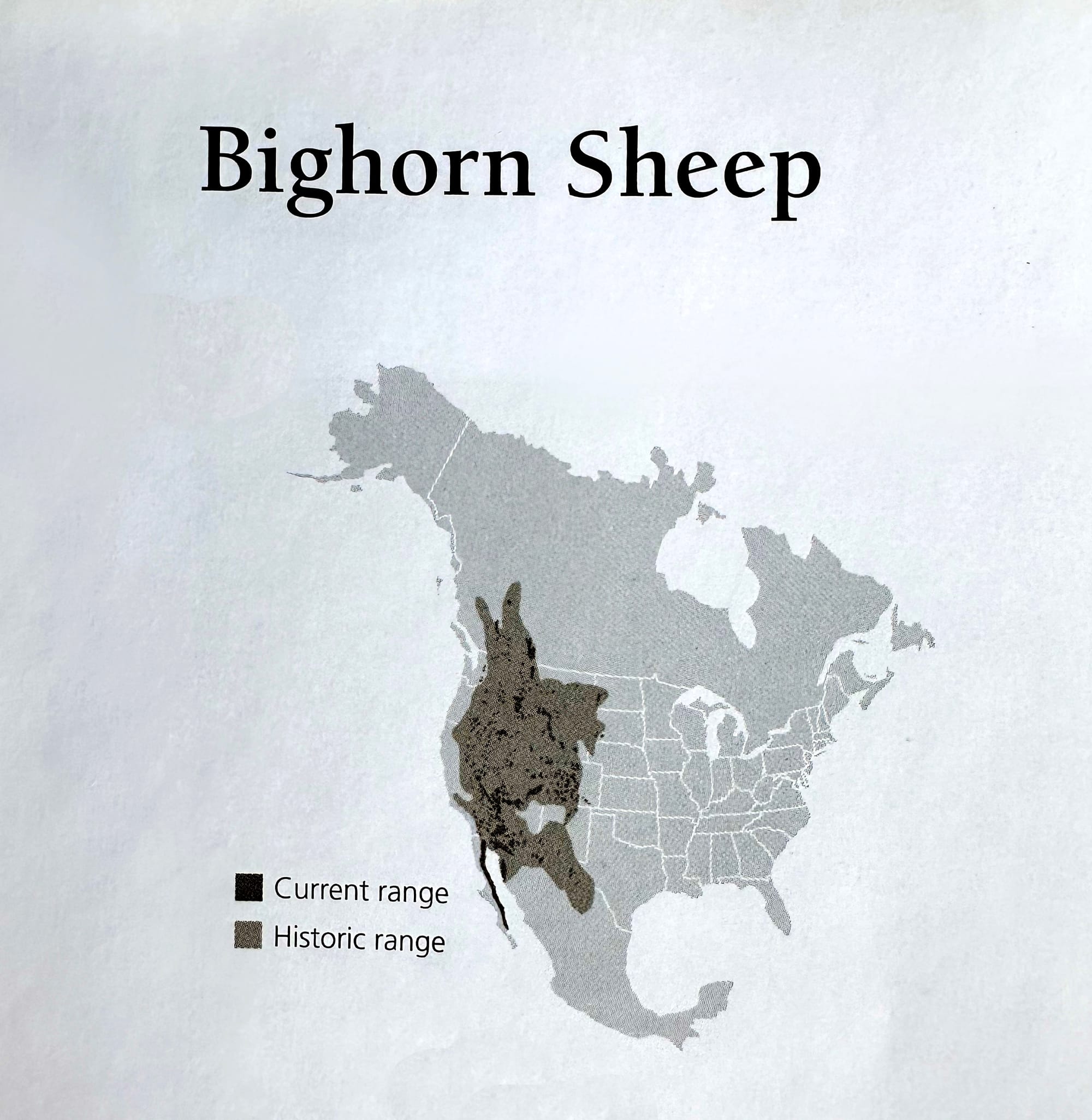

Bighorn sheep are one of North America's most distinctive hoofed animals. Favoring dry mountains and open areas, millions of bighorns once roamed vast stretches of the American West, with early explorers describing thousands being found in some areas.

Today's bighorn sheep numbers have plummeted, and while they're still relatively common, they're now almost entirely restricted to isolated bands or "population units" scattered throughout some of our more remote mountain landscapes and national parks.

For an animal that can navigate the most rugged mountains and handle temperatures down to -30°F, bighorn sheep are surprisingly fragile. Not only are they more vulnerable to certain respiratory diseases than human infants, but they are still hunted in many areas and readily disturbed by people.

People love to see these unique and majestic creatures, and Jasper National Park in the Canadian Rockies is one spot where bighorns are fairly common and found in predictable locations.

During the summer and early fall, bighorn sheep typically separate into two bands. Older rams head for high alpine meadows where they feed on high quality grasses and forbs to build up their strength for the exhaustive mating season in November and December.

And, at the same time, females and youngsters seek out safer grazing areas in low-lying valleys.

Females and youngsters gathering in a valley bottom in Jasper National Park. Photos by David Lukas

Although bighorn sheep spend most of their day grazing, or resting and chewing their cud, males also spend a lot of time during the summer establishing and maintaining their dominance hierarchies. Males are famous for ramming their horns together but this is rare because they do most of their jockeying in far more complex and subtle ways.

Dominance over another male can be signaled by resting your head on his back or butting him with your horns. Photos by David Lukas

The interactions between three males is what led to the situation I mentioned at the start of the newsletter. In this case, I was with a well-known herd of males who are watched all day long by a steady stream of hikers. In general, people watch from a respectful distance, but this time it didn't matter because these three rams looked over and started quickly and repeatedly closing the gap, closely following people as they backed up step by step.

At first glance it seemed like these rams were aggressively approaching and I could hear people around me yelling things like "watch out they're angry" or "they're charging us!" I'm no expert, and I could be wrong, but I saw something else going on.

What was happening was that one of these males was being relentlessly and mercilessly picked on by the other two males. No matter where he went, or how he tried to ignore them, they wouldn't stop bullying him. At some point, he finally turned and started trotting towards the handful of people who had gathered at a distant viewpoint. Rather than charging aggressively or angrily, it felt to me like he was desperately trying to use the presence of people to shake his pursuers.

Ultimately I can't be sure what was happening, but what I learned from this experience was the value of taking time to put myself in the animal's frame of mind. There was clearly a story going on here, but rather than reacting impulsively, I wanted to see what I could learn by paying close attention and treating these beautiful animals with the empathy they deserved.

Member discussion