Healthy with Frog

Two frog stories appeared on my radar this week, and although the topics are unrelated, they are both linked to human health, so I decided to include both of them in today's newsletter.

The microbiome is a subject that has long fascinated me, and I have several microbiome topics on my list of future newsletter stories. So, why is this such a fascinating topic?

I think it's incredible that our bodies are composed of more bacterial, fungal, and viral cells than our own cells, and that these non-human cells contain 100-150 times more genetic information than our own cells. In fact, when you look at the physical bulk and genetic software of our bodies, it turns out that we are more microbe than human.

We have been co-evolving with these microbial partners for hundreds of thousands of years, and in exchange for nourishment and a home, these bacteria, fungi, and viruses do the heavy lifting of managing and protecting the functioning of the human superorganism.

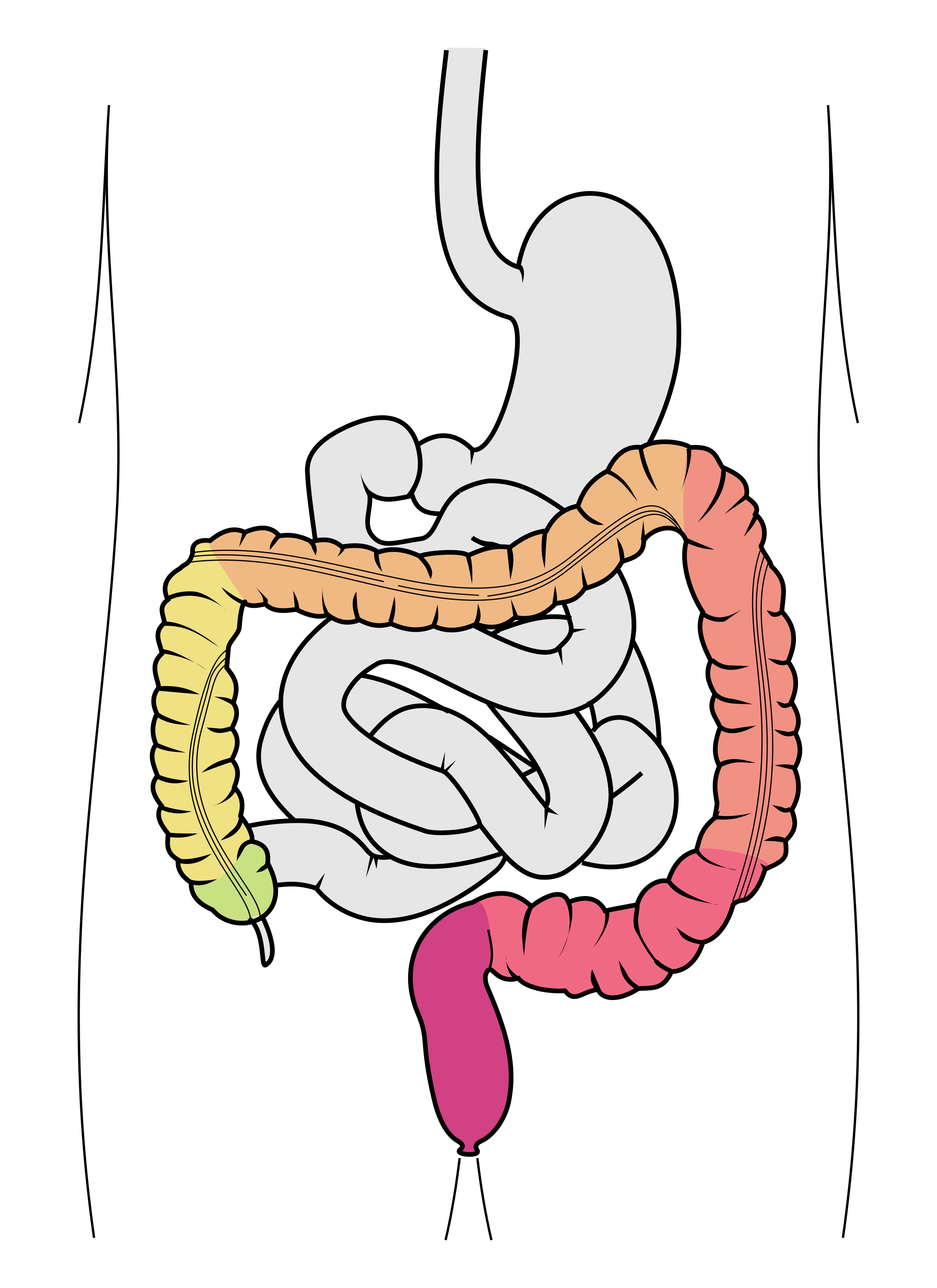

With the advancement of new technologies over the past 20 years, scientists have just begun to scratch the surface of what's going on here. It is now known that the human body is home to an estimated 3 trillion bacterial cells, with the vast majority of these cells living in the large intestine, where they impact many of our bodies most significant functions.

One of many YouTube videos exploring the human microbiome.

I can't go into all these functions, and they are not the subject of today's newsletter, but it turns out that microbes living in our gut do things like managing our behavior and moods, including pain, depression, and anxiety. They also activate neural pathways, and moderate which signals are being sent to our central nervous systems.

And, because their lives and well-being depend on the health and well-being of their human home, microbes play key roles in how we digest food and fight off diseases. For example, when microbial communities in our large intestines get out of balance, it can trigger inflammation and debilitating diseases.

Of particular note are the high percentage (at least 20%) of cancers that have been linked to microbial imbalances, and this is where frogs come into the picture. It turns out that frogs, along with other amphibians and reptiles, very rarely develop cancerous tumors despite enduring extreme cellular stress (including changing from aquatic larvae to terrestrial adults) and living in pathogen-rich environments (such as stagnant water), so a team of researchers decided to take a closer look at the microbes living in frog intestines.

They isolated nine gut microbes from a range of amphibians and reptiles that demonstrated anti-tumor properties and found one species of bacteria (Ewingella americana) living in frog guts that very quickly eliminated 100% of the cancerous tumors in laboratory mice. Even more encouraging, Ewingella americana lingered in mice for less than 24 hours but seems to convey long-lasting protection against new cancer cells.

What makes this discovery so significant are the novel ways that the bacteria tackle tumor cells, which opens up exciting possibilities for new cancer treatments. First, Ewingella americana targets the unique low-oxygen environments that exist inside tumors, and because tumors suppress the body's immune response the number of bacteria exploded 3000-fold in hours. Secondly, the bacteria activate the host's own immune response, which allowed the bacteria and host to work in tandem to quickly overcome tumor cells.

There's much more to this story, and I'll include some links below, but I think it's incredible that a microbe that helps manage the health of frogs can share their anti-tumor properties across phylum and stop cancers in mammals! And this is just the beginning of what we're learning about the microbiome!

Further Reading:

There are countless articles about the microbiome, but this Wikipedia entry is a reasonable starting point. At the other end of the spectrum, here are two highly technical papers that provide an overview of what's currently known, Microbiome and Cancer and The Gut Microbiota at the Service of Immunometabolism. The frog story is summarized in this well-written, popular article, and here's a link to the original research.

A Frog Tale:

At risk of having this newsletter run too long, I want to include another frog story as a cautionary note. I recently read a news story titled Inside the Aftermath of the 'Frog Apocalypse' that described how populations of malaria-carrying mosquitoes in Central America exploded after frog populations were decimated by a deadly fungus. The premise of the story is that tadpoles eat mosquito larvae so when frogs die out more mosquito larvae survive to become adult mosquitoes that spread malaria.

That sounds like a neat and tidy story, except that tadpoles don't eat mosquito larvae. Tadpoles are designed to eat plant material and are not even equipped to chase down fast-moving mosquito larvae if they could eat them.

I tracked down the original research paper and immediately noticed that when the researchers talked about amphibians and mosquitos they were talking about salamander larvae, which eat up to 400 mosquito larvae per day. In this study, they briefly mention one species of frog (out of hundreds of species) whose tadpoles can sometimes eat mosquito larvae, but that's a far cry from how the popular article portrayed this story.

I take this as a reminder of how carefully we need to read popular stories and how we need to watch out for erroneous descriptions of the natural world. I take this seriously because my job is to find and share fascinating stories, and it matters to me to be as truthful and honest as possible in the midst of all the slop that exists in the world today. I won't always get it right, but I'm doing the best I can!

Member discussion