Delaminating the Mantle

To the naked eye, the Sierra Nevada is one of the world's most dramatic landscapes, but the real drama occurs under the surface and what scientists are discovering there goes a long ways towards explaining how the Earth's surface evolves.

The Sierra Nevada of eastern California is one of the world's great mountain ranges, stretching 400 miles with more than 100 peaks over 13,000 feet and 13 peaks over 14,000 feet, while its eastern flank towers two miles over the desert floor near Mt Whitney. But this mountain range has long mystified scientists because these soaring peaks rose unexpectedly fast 3-5 million years ago.

Mountains like the Sierra Nevada are part of the Earth's crust, an outer layer of rocks floating on top of the mantle that separates solid rock on the surface from the planet's molten core. But the crust is not uniformly solid because under certain conditions, parts of the crust can melt and separate, with lighter materials moving to the top of the crust and denser materials sinking and merging with the upper mantle.

Over time, those heavier layers of lower crust and upper mantle can peel off and sink towards the center of the Earth in a process known as delamination or lithospheric foundering.

In areas where the crust is heavier it sits lower and is covered by oceans, in areas where the crust becomes lighter due to delamination it rides higher and forms continents.

What's remarkable is that scientists have recently documented this precise process happening in the southern Sierra Nevada. By sending sound waves through the Earth's crust, scientists now know that the Sierra Nevada's root has peeled away, reducing the foundation of the mountain range from 40 miles thick to a present-day thickness of 20 miles.

It's now widely accepted that the loss of this heavy "root" is what prompted the Sierra Nevada to pop up suddenly, like a cork unburdened from a massive weight that had been holding it down.

History of the Sierra Nevada

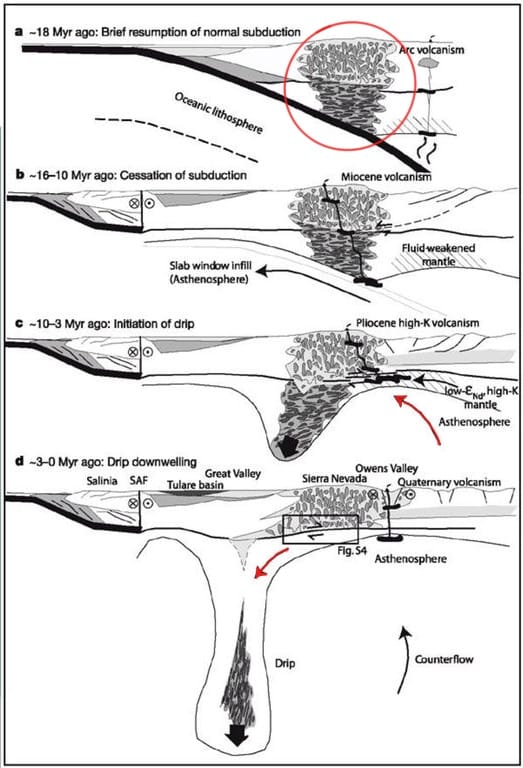

The Sierra Nevada formed as an ocean plate subducted under the edge of North America and melted. This molten rock cooled into a massive granite batholith (red circle in first image) that later emerged as surface rocks eroded to expose the tip of the batholith.

Starting 10 million years ago, rising molten rock from the asthenosphere began to push the root of the batholith to the west and southwest (red arrow in third image), eventually shearing it off. Released from its heavy foundation, the rest of the batholith rose very quickly to its current height about 3 million years ago.

Meanwhile, the sheared root has begun a slow fall towards the Earth's core (red arrow in fourth image) and because the rising batholith is a rigid block it broke along fault lines at its margins and is now tilting to the west.

This may seem somewhat esoteric, and restricted to one mountain range, but this process is happening in many places around the planet, and it helps explain how the Earth recycles the materials it is formed of.

The recycling of the Earth's rocks would grind to a standstill if the crust was forever trapped on the surface, but what happens instead is that large portions of the crust are continually being delaminated and cycled back into molten rock deep underground.

One way to look at this is that all of the processes we see on the surface—the emergence of continents and the rise and fall of mountains—are being mirrored under the surface as lower portions of the crust delaminate and sink, or melt and drip, into the interior of the Earth.

It's all part of the larger homeostasis that keeps the Earth in balance as its hard crust is sculpted both above and below and materials are continually being recycled in an ongoing feedback loop.

Member discussion