Contributing to Zombies

Aquatic worms growing up inside terrestrial insects use devious means of getting back to water.

I first learned about horsehair worms while on a nature walk with the legendary Marin County Open Space naturalist David Herlocker. When our group discovered a dead Jerusalem cricket on the trail, he explained how parasitic worms that were living inside the cricket had reprogrammed the cricket's brain so the cricket emerged from the ground and started wandering aimlessly until it encountered standing water. At this point, the worm emerged to complete its life cycle in water.

The shock of this story was compounded when we reached the edge of a pond and found another dead cricket with a long, horsehair worm wriggling in the water nearby.

Ever since, I've thought about this story every time I see a Jerusalem cricket stumbling around in the daytime. These scary-looking insects spend their lives underground, with occasional nocturnal forays, as they feed on decaying plants and animals.

You rarely see Jerusalem crickets unless you're digging in your garden, or turning over boards in your yard, but when rains return in the fall, you're much more likely to see them wandering around.

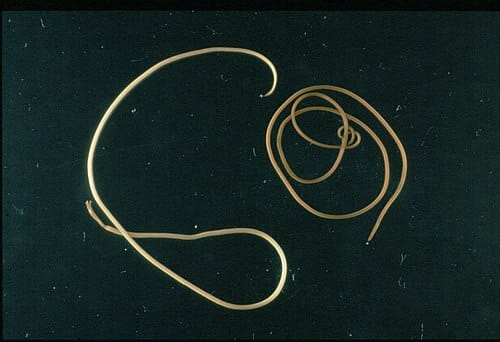

Horsehair worms, also known as hair worms or Gordian worms, are bizarre critters. They are one of only three animal groups that specialize on an entirely parasitic lifestyle, but they take it a step further by starting their life as microscopic larvae living in water. These larvae indiscriminately infect almost any type of intermediate host living in the water, including both vertebrates and invertebrates.

Once inside an intermediate host, the larvae readily penetrate the host's gut wall and then turn into a cyst attached to the outside of the gut. At this point, the almost indestructible cyst waits for its host to end up on land and die. For example, if the host is the larvae of an aquatic insect, the cyst survives the insect's metamorphosis into a flying insect that eventually dies and ends up decaying on the ground.

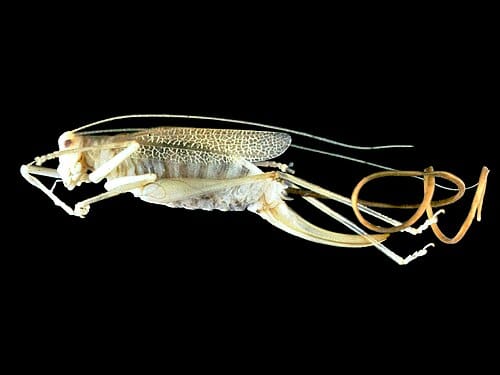

At this point, the cyst needs a cricket, grasshopper, beetle, or cockroach to start nibbling on the decaying carcass, or a praying mantis to eat the insect while it's alvie, and once inside the new host, the worm emerges from its cyst.

The worm now begins absorbing all the host's lipids (which are the insect's source of energy). This prevents the host from growing and reproducing, even as the worm grows longer and longer (some horsehair worms can grow to over six feet long).

In the case of male crickets, this means they never reach adulthood and start singing. One theory is that singing crickets attract the attention of predators, but the worm needs the cricket to live long enough for the worm to reach adulthood.

Upon reaching adulthood, the worm somehow modifies the host's brain (both changes in brain structure and protein production have been documented) so the host begins wandering erratically. During these wanderings, there's a chance that the host encounters a body of water, at which point the worm almost immediately emerges from the host's body and enters the water, where it seeks out other worms and begins mating.

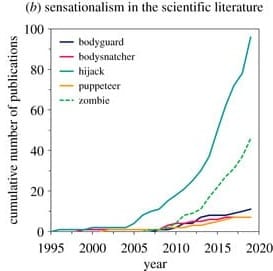

One key question is how we name and describe this incredible relationship. In fact, I chose the title for today's newsletter after reading a critical analysis of how the cycle of fake news prompts sensational headlines and word choices, and how this influence bleeds back and forth between scientific work and media outlets.

Writers regularly use words like zombie, mind control, and hijack to describe crickets and horsehair worms, but the science behind this story is far more nuanced than that. For example, many writers have described the crickets being driven to water and forced to commit suicide by the worms, but the science is far from conclusive. In fact, one doctoral student found that all but one of 22 female crickets she observed survived and went on to finish growing up and living a normal life after their worms emerged. Other researchers have been studying whether the host insects cooperate with worms by taking them to water so the hosts can free themselves of their burdens.

There's a lot more going on here; only six of the world's ~360 known species have been studied for any period of time, and it's thought that only a fraction of the world's horsehair worms has been discovered and named. Horsehair worms are also incredibly hard to find; in one study, adult worms were only found in one of 94 streams surveyed, even though horsehair worm cysts were found in aquatic snails in 70% of these streams.

If it weren't for Jerusalem crickets emerging to wander around in the daytime, you'd hardly know that horsehair worms even existed!

Member discussion