Binding Sand

On a recent outing, I posed myself a challenge and learned something fascinating. Stopping at each plant along the trail, I used my phone to search the internet for this question: Do the seeds of this plant produce mucilage?

To my amazement, the answer was yes for every species, genus, and family of plants I searched on (except for sedges). Granted, my sample size was relatively small, but it pointed to something I never realized: seed mucilage is a fundamental feature of the plant kingdom.

So, what is mucilage and why is it important for seeds.

Seeds are a plant's most important investment, but they are extremely vulnerable to predation, so it matters to a plant if its seeds are eaten or nibbled on.

Seeds are highly condensed packets of fats, proteins, vitamins, and minerals designed to fuel the germination and growth of new seedlings. As a result, many insects (especially ants), rodents, and birds eat every seed they can find, and the number of seeds lost to predation is astronomical.

Not only that, but many plants produce seeds that are tiny and easily displaced by wind or water. In one study, 60-90% of the seeds on a shallow slope were washed away in a single hour of heavy rain, and across a 150-acre plot an estimated 1.3 million seeds ended up in a nearby river.

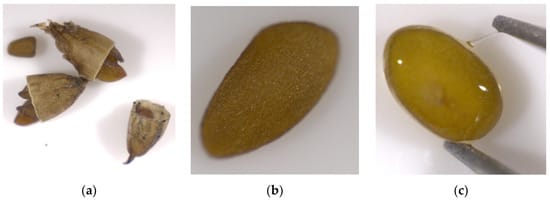

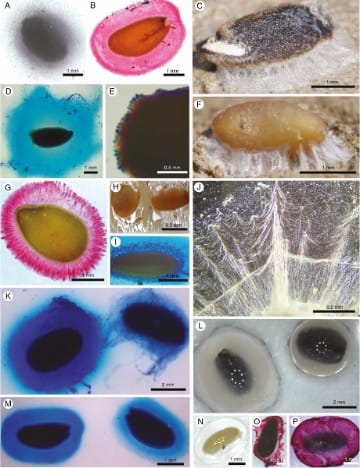

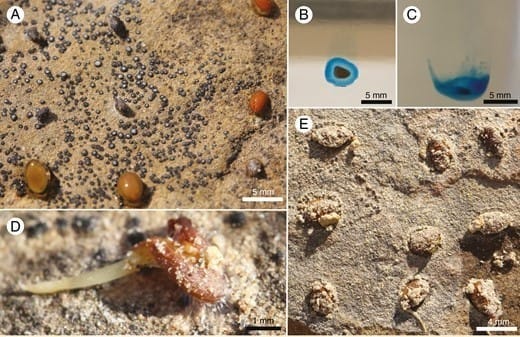

The solution is that the seeds of many plants get wet they produce a slimy, sticky coat of mucous, and this mucilage plays several key roles. On hard surfaces this coat of sticky polysaccharides glues seeds in place, and on loose sandy substrates, the seed ends up covered in heavy sand particles (what is known as psammophory or sand armor).

This binding action is so effective that it will take 280 times more time and physical force before a seed can be dislodged. Plus, it forces seed predators to exert a lot more time and effort into harvesting and removing sand before they can eat the seeds. In one study, it took ants 10 minutes to remove enough heavy sand from a flax seed to physically carry it to their nest.

Other benefits might include camouflaging the seed so it's harder to spot and helping keep seeds and future seedlings hydrated. One study also pointed to the number of seeds that survive passage through a bird's digestive system when they're protected by mucilage.

Psammophory is surprising common in the plant kingdom. In addition to slimy seeds, many plants have sticky stems and leaves to collect dust and sand particles as an armor against herbivores. For instance, caterpillars eating sandy leaves endure constant wear and tear on their mandibles, so they grow more slowly and pupate at smaller sizes.

I'm currently reading Zoë Schlanger's book The Light Eaters, in which she explores some of the research into plant consciousness and intelligence. I don't know if using sand as a tool counts as consciousness or intelligence, but it seems pretty smart to me.

More Resources:

These two papers go into more detail on today's topic,

Binding Sand in the News: https://www.earth.com/news/process-microbes-turn-desert-sand-into-fertile-soil-in-just-10-months/

And this YouTube video is a fun overview,

Member discussion